Written in Darkness

A far too personal end-of-the-year contemplation of Jane Austen’s Darkness by Julia Yost

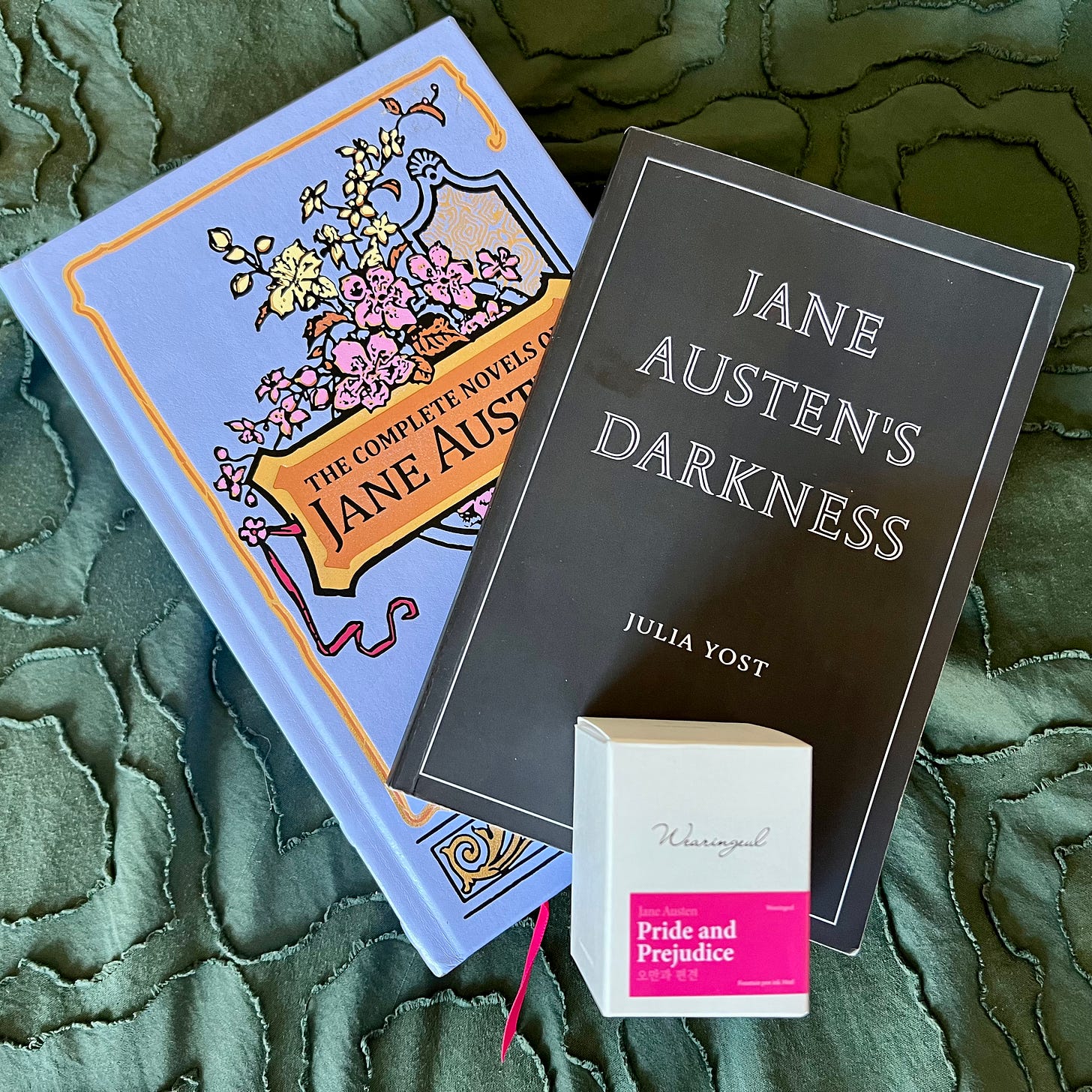

Jane Austen’s Darkness by Julia Yost

(Wiseblood Books, 2024) $10 On sale for $5

Happy holidays, dear readers. This is more of a confession than anything else. I had wanted to write a proper review of Julia Yost’s Jane Austen’s Darkness for over a year. It came out in September, 2024, just a few months after I had gone on a 6-day retreat to talk about Pride and Prejudice with members of the Close Reads community. It seemed like good timing, but I wanted to make sure I had read all of Austen’s novels before I wrote a review. In the meantime many thoughtful reviews had come out by Tessa Carman at Mere Orthodoxy, Peter Leithart at First Things, Geoffrey Reiter at Orange Blossom Ordinary, Gerardo Muñoz at Infrapolitical Reflections, Natasha Duquette at Dappled Things, Jon D. Schaff in Current, and Adele Gallogly at Christian Courier. Much of what I could say has already been said: that this is a book worthy of your time because Yost’s concise and informative analysis shines new light into the dark societal forces that create much of the tension in Austen’s novels. Even if one disagrees with Yost’s findings, her book succeeds in refreshing our perspectives for future readings, not just of Austen’s books but for other books set in 1800s England.

Both the black cover and the title of this Wiseblood monograph are meant to be provocative. Most people read Austen for its humor and wit, and if one were to slap a pithy, barely accurate label on her work I suppose one could call her books Regency romances. However, as many Austen fans know, there is so much more going on in her novels. In reading Julia Yost’s book, I have realized why I have lacked the ardor of Austen’s most passionate fans, but it isn’t a fault of the author. Austen is brilliant. It is just the books themselves reveal the darkness in myself, my anxieties of interacting with a world with social expectations I barely understand and often fail to navigate on the level that people expect me to.

Over the past couple of weeks I have repeatedly tried and failed to write a traditional review of this book. My self-imposed deadline was Jane Austen’s 250th birthday, which I had obviously missed. Not only that, I feel I have failed to write a satisfactory piece of criticism over the past several months because my personal life and subsequent my mental disassembly has been bleeding into my critical writing, creating a chaotic dashing from one impression to another and never reaching the point where a real essay forms. As one can imagine, this is also not helpful as a writer on Substack.

I had a similar depressive episode when I attended a Close Reads Pride and Prejudice retreat in 2024. Discussing a book where “hatred” simmers beneath the cool veneer of gentility is something that affected me more than I thought it would. In Jane Austen’s Darkness, Yost often refers to war psychologist D.W. Hardings’s essay “Regulated Hatred” to explain how things are not always as they appear when it comes to the behavior of seemingly courteous characters:

Social convention helped everyone to stay “on reasonably good terms” despite their natural depravity—and thank heaven. But a consequence of this settlement was that detestable people could pass as ordinary, polite, prestigious.1

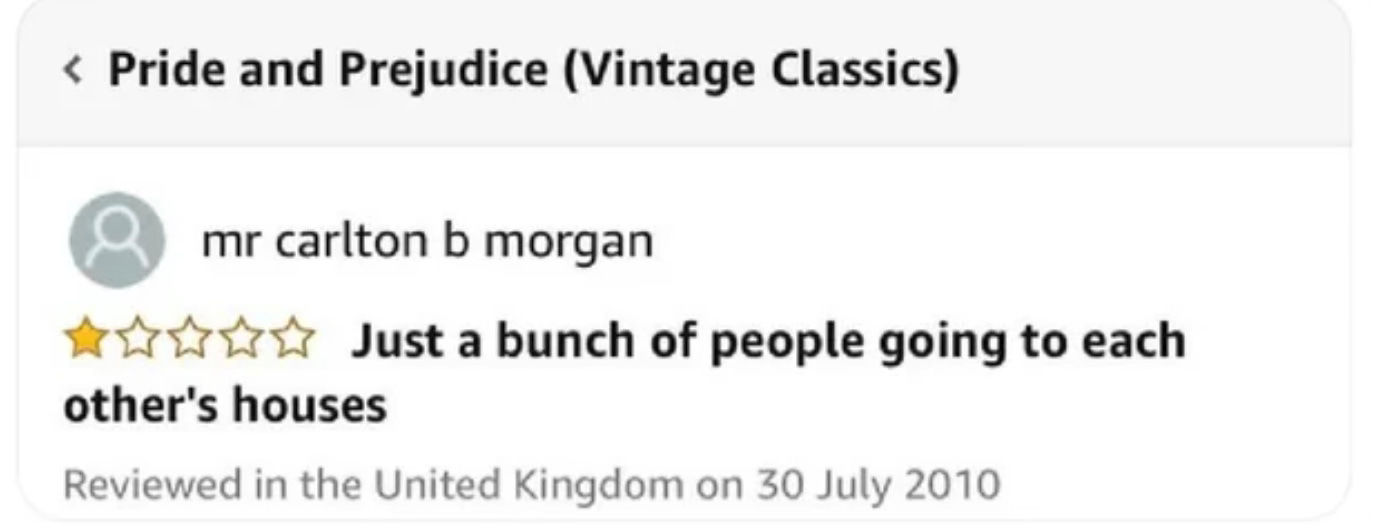

As in the case of some of Austen’s heroines, this realization can contribute to a sense of paranoia. And this is what happens to me on a regular basis. In reading Yost, I have realized that I have gravitated toward fiction that deals with violence, war, sci-fi and fantasy because the threats are more obvious and straightforward. Purely social dangers and traps are harder for me to comprehend. Remember the viral Amazon review of Pride and Prejudice?

Although humorously reductive, “Just a bunch of people going to each other’s houses” reflects the fact that Pride and Prejudice is a book whose drama is socially constructed.

During the retreat I was sitting with a group of women and someone asked, “Would you rather live during Jane Austen’s time or now?” Many of my friends seemed to want to go back in time. I suppose they viewed the lack of smartphones and distracting technology as an improvement on their lives, allowing more time to read books and play some tunes at the piano-forte. I imagine that they were picturing themselves in the same class as a Dashwood or Bennet sister, and not, let’s say, a washer-woman or a governess. When it came to my turn I asked, “Would I still look Filipino?” Racism isn’t really an issue in Austen, but would it pose a complication of sorts in the case of this question? Also, the fact that some of the wealth in Austen’s novels was earned through slavery, as in the case of Mansfield Park and Emma, is not lost on me. When Austen depicts a morally upstanding heroine like Fanny Price in Mansfield Park, Yost says that “her morality is slave morality. Her accent on denial and constraint is not extricable from her self-image as a nobody who deserves nothing.” (22) This is a pointed comparison seeing as her benefactor, Sir Thomas Bertram, builds his wealth off off of a plantation in Antigua.

My fixation on issues of racism and inequality are often more prevalent during depressive episodes. And let me be clear, I do not disagree with my friends’ desires to live in whatever time they want to. The problem with these low states is that it is hard for me to entertain whimsical "what if” games that are lovely thought exercises for others. The problem isn’t others; it is me.

It offends my sense of justice to see mediocrity succeed over meritorious characters, and this is routinely depicted in Austen’s novels. However, the heroines, despite their flaws, get their happy (or maybe happy-ish) endings. It has occurred to me that I may not be in the right season to read Jane Austen, just as when I was 18-years-old I was not in the right season to read Anna Karenina.2 It is quite incredible how one’s mental state can impact one’s ability to delve into literature.

I suppose this last post of 2025 is meant to say:

Happy 250th birthday, Jane Austen;

I found Julia Yost’s Jane Austen’s Darkness very thought provoking and a worthwhile read;

I’m in a dark season, and any encouragement is greatly appreciated;

I love you all and I hope you have a safe and joyous end of the year and beginning of a new one.

I am confident that with enough time I will be able to climb back out of this — God willing and the creek don’t rise.

Thank you, as always, for reading. Especially this post. I am determined to make the next entry more useful and cheerful.

On page 5 Yost cites D. W. Harding, Regulated Hatred and Other Essays on Jame Austen (Atlantic Highlands: Athlone Press, 1998), 160.

How to Read a Novel in 30 Years

I am not sure if you’ve noticed, but my writing schedule has become less consistent lately. The kind, generous writer Sarah Styf had asked recently if I had posts that seemed “evergreen” for these occasions wh…

Zina, I can understand this place..."my personal life and subsequent my mental disassembly has been bleeding into my critical writing, creating a chaotic dashing from one impression to another and never reaching the point where a real essay forms." Especially the chaotic dash from one impression to another. I sometimes find it disturbing not to land one in place but mostly the concern that I will remain dashing about. But eventually through reading just where my fingers land and then writing out passages from books or poetry that strike me..slowly some threads begin to emerge into a more wholistic view or a focus of some sort. Sometimes just time to take in what seems to be random input forms...All the best for 2026...keep writing please whatever...

Thank you for your honesty, Zina. Certain books have overwhelmed me in the past, especially the strange novels of John Cowper Powys. He is a very disturbing writer for those who often feel close to the edge - as I used to feel.