How to Read a Novel in 30 Years

On Anna Karenina, mental illness, and reading as if your life depends on it

I am not sure if you’ve noticed, but my writing schedule has become less consistent lately. The kind, generous writer

had asked recently if I had posts that seemed “evergreen” for these occasions when I cannot post something new, and I had not responded to say that I do. I have a collection of twenty essays saved in my Drafts folder, not fully finished, sitting there in that virtual corner like a mottled silver tea set waiting for a visit from the queen as an excuse to be polished. That last bit of refinement seems to be a big enough deterrent for me to not publish, and I am trying to honor the energy that I have.This morning,

had written a beautiful post about giving yourself permission to rest—and I have been feeling this lately in regard to my Substack writing. It is midwinter, and this is the season when my life frosts over after the candle lights of holidays and holy days are blown out. It is a hunkering down time—when my written words crystallize like breath on a night-chilled window.In truth, I am also likely suffering burnout from an emergency that had come like a sudden fire in autumn and somehow has kept itself in a smoldering state that threatens to rage if left unattended.

And of course my friends ask, “Are you taking care of yourself?”

Yes, I am because self-care is au courant. And if I am anything, I am at the very least fashionable.

I am reading. This is my self-care when my writing fails me.

The fantastically prolific art+mental health writer

had asked me recently about my new year’s resolution to have a threshhold instead of a surpassable goal for the number of books I read. Basically, in 2024 I plan to read at least 42 books but not to exceed 52. This is so I don’t feel the need to compete with others or myself, and I allow myself to develop a relationship with the books I spend time with. It also allows me time to read longer books in depth. This idea reminds me of this note by :It appears that 52 is my Dunbar’s number for books. That is roughly one book a week which allows fewer days for shorter books and more time with longer ones over the course of a year.

But in truth, the ability to read has left me at different times of my life. Those were disastrous years. It happens to many people, and for a long time it happened to me.

This is why it took me 30 years to read one book.

A while back I had written a post about how to read a long novel in a short amount of time. It was a guide for my friends who were going to attend a Dostoyevsky retreat with me, and they had fallen behind in their reading.

How to Read a Long, Complicated Novel Very Quickly

Hello. I am so glad you are here. I will leave some personal news at the bottom of the post.

However, this post is going to be the opposite. How do you live a long time with a story, how to sip carefully from it like a canteen of water while you are lost, wandering the desert…

In 1992, I was 18 and a freshman in college.

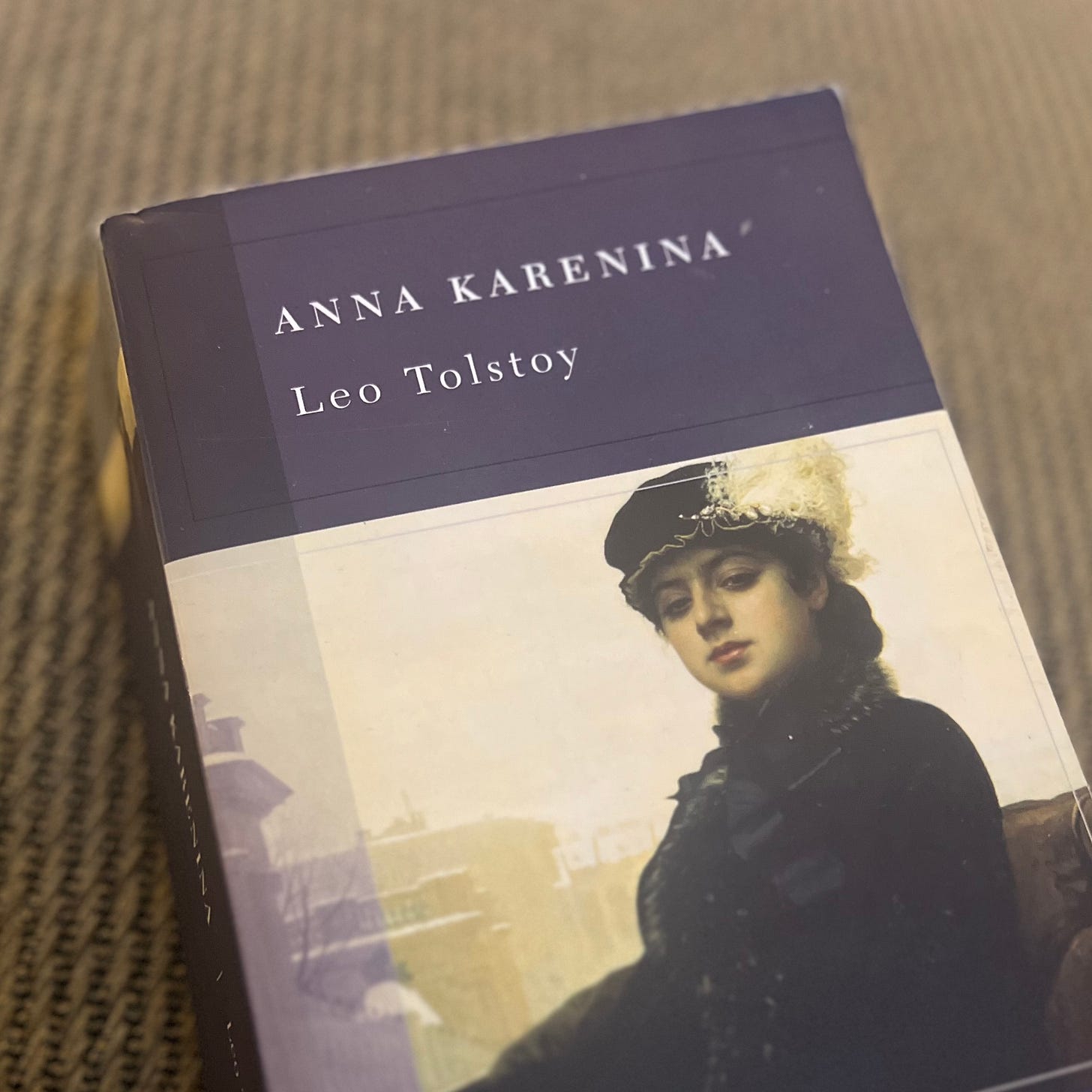

Since I would be traveling to and from Boston and Washington, DC via Amtrak trains, I thought, “Wouldn’t it be interesting to read Anna Karenina whenever I had to travel on the train?” I had always wanted to read Tolstoy, and seeing as how I knew the ending, I thought this choice of novel was morbidly appropriate. (I may have to mildly spoil the story line if you have not read it.)

Not only did I read it on long train trips, but I had it with me on the Metro and whenever I had snatches of time—which became fewer and fewer as my studies, internships, and paid work took bigger slices of my waking hours. However, my mental health declined each year I was at school until the last semester of my senior year when I lost the ability to read.

I had gone from being one of the most active and best prepared students to someone who could note even read a single essay. I monopolized professors’ office hours with my crying. I didn’t know how I was going to graduate. And then my housing for the last few months fell through, and I was effectively homeless. And to make matters worse…

Anna was pregnant with Vronsky’s baby and I didn’t know what was going to happen!

With the help of several good friends and my boyfriend-now-husband I was able to graduate and slowly recovered my reading. But that was temporary.

What I didn’t know was that I was descending into a depression so severe it would become, for periods of time, disabling. All of this will sound impossible to most people because of the jobs I had, and how well I did some of them. But it is amazing how much you can compensate if you have a good enough memory, an ability to visually match patterns, and worked with teams of people who read and repeated many things to you.

My reading would return, but my creative writing would not come back until my mid-40s. In the meantime, I could not make any significant progress with the story of Anna. My relationship with Tolstoy was on hold until I could get better, but I was determined to come back.

Through the years from my college days until I had my fifth and last child at 40, my husband has been supporting me through terrible times. As a 21-year-old he was the first to suggest therapy. When I didn’t have money or transportation to see a psychiatrist he brought me to appointments. He helped me make my mental health a priority, which is something no one else had done. And when I said I needed to go the hospital because I said I was going to kill myself if I didn’t, he brought me in the middle of the night and made sure I got the help I needed. He was not going to let me despair.

I was not Anna—was never going to be Anna. Unlike Vronsky, my husband never gave me any reason to be jealous. Unlike Karenin, my husband was never cold and cruel to me. He has always made my life his life—and his life is mine. Not in a codependent way, but in an interdependent way. We are together because we have something to offer the other person.

It is said that one of the most important decisions anyone ever makes is who to marry. Based on my experience, I would agree.

I was 48 when I finished reading Anna Karenina.

With the children in all stages of growing and learning, I had put away Leo Tolstoy in favor of Eric Carle, Shel Silverstein, J. K. Rowling, and Kate DiCamillo. It was not until

had Anna Karenina in their reading list that I picked it up again and finished it.To have grown up with a single story and the longing to finish it is not unlike casting yourself in the role of Scheherazade, with suicidal ideation is the Persian king who threatens to behead you in the morning. As Joan Didion wrote, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

How did this novel keep me alive?

“If it is true that there are as many minds as there are heads, then there are as many kinds of love as there are hearts.”

- Tolstoy, Anna Karenina

When I chose this novel as a teenager, I did it with the end in mind—with thoughts of the train and a tragic character. What I didn’t realize was that this story was going to be about marriage and all its human complications: the duties and desires, the betrayals and jealousies. Every character in the novel loved with a different heart and showed that different hearts break in different ways.

I was kept alive by stories—because the people on the page were safer than the people in my real life. When it hurt too much to be in the world I knew that if I could just read again I could be in an another place where people were figuring out how to be better. And if they were not going to get better, then I could just learn what not to do by their example.

Although I have finished the book, I do not think I will ever be done with Anna Karenina. As Heraclitus said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man.” And the same can be said about who you are when you pick up a book you have read before. It is not the same book because you are not the same person.

An 18-year-old college student is not a 28-year-old overworked professional or a 38-year-old mother with postpartum depression or a 48-year-old reinvented poet and mother of adults and children. None of these women are the same person, and a masterpiece will say something different to each iteration of the same soul.

So how do you read a single novel in 30 years?

My answer:

With a generous heart.

With kindness to yourself for going at the pace you need to.

Without comparing yourself to anyone else—even your previous able-bodied, quick-learning self.

One word at a time, with as much time as you need to take.

And now a question:

What are you going to read?

Zina, apologies for taking a few days to get to this after you referred me to it. So glad you did! So many things occurred to me to say about it as I read that for the sake of brevity, I need to reduce them to this: how fully human this essay is, vulnerable and sharing and wide in its references, infused with the love of books and reading and relationship, in such delicate, fluid writing, it was an easy and touching pleasure. I can't not read you now! (Aha, that was the plan. ;)

Zina - I appreciate the courage you show in being vulnerable about your life. The best writing comes from a place of deep experience, often painful. I found this a very compelling essay.

My main read for this year is the complete body of work by John Steinbeck. I fell in love with his writing when I read East of Eden a couple years ago.