Jesus, En Folkefiende

Drama as part of the Catholic Mass. How reading Ibsen's An Enemy of the People becomes unsettling preparation for my role this Palm Sunday.

First, thank you to

whose note reminded me that this past Wednesday was Henrik Ibsen’s birthday.Henrik Ibsen (20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) is the most frequently performed dramatist after William Shakespeare, and in 2006, the centennial of Ibsen’s death, A Doll’s House was the most performed play in the world.1

This past week another one of Ibsen’s plays, an Amy Herzog’s adaptation of An Enemy of the People starring Jeremy Strong (Succession) and Michael Imperioli (The Sopranos, The White Lotus) made news because it was disrupted by climate activists during a press performance.

From The Vulture,

On the evening of Thursday, March 14, three protesters from the climate-activist group Extinction Rebellion stood up during a town-meeting scene in a press preview of An Enemy of the People to interrupt the play with speeches of their own about the climate crisis — imploring the audience to believe scientists, calling attention to the harsh sentences for activists Timothy Martin and Joanna Smith (arrested for smearing paint on a Degas in the National Gallery), and repeating the phrase “No theater on a dead planet.”

“This play highlights that climate activists are not the enemy,” Laura Robinson, a spokesperson for the group, said in a statement. “But why are we being treated as such?”

Some of those in attendance thought these disruptions were actually staged by the director Sam Gold as part of the performance, but this was not the case. If you are curious as I recommend reading this Time Out article about the incident which also contains videos from that night. Like this one.

For those of you who do not know, the plot of the play lends itself very well to a modern environmentalist/climate crisis interpretation. The protagonist is a doctor who has discovered that a health spa that has opened up in town is being fed with water contaminated with dangerous levels of bacteria due to industrial pollution.

I have not seen this performance, but I know that changes were made to the script. In Herzog’s version, the doctor is a widower as opposed to married, and the role of the daughter Petra is a combination of the mother-daughter roles in Ibsen’s original creation. I am sure that there were other choices that Herzog made—some of them likely in order to hone in on an environmental reading. The adapting playwright has a right to make these types of changes as long as it doesn’t degrade the integrity of the original work.

Case in point, I have been reading Arthur Miller’s adaptation of An Enemy of the People, not knowing about Ibsen’s birthday or the current revival on Broadway.

Miller describes several changes he made from Ibsen’s play—cutting lines that had some fascist undertones in translation. Remember that his version was performed not long after the end of the Second World War, so Miller’s concerns had more to do with the abuse of individuals at the hands of authoritarian regimes.

In fact, the theme of a central figure who holds fast to the truth despite the repercussions from authority can be seen in one of the greatest Greek plays, Sophocles’ Antigone, whose heroine acts in accordance to her her beliefs knowing that she will be punished by Creon who is deadly resolute in his desire to maintain order and peace of the state.

The title of Ibsen’s play in Norwegian is En folkefiende, which is not only more alliterative but more efficient than the two Latin words from which we get the term enemy of the people: hostis publicus. From Wikipedia,

The terms enemy of the people and enemy of the nation are designations for the political opponents and for the social-class opponents of the power group within a larger social unit, who, thus identified, can be subjected to political repression.

This brings me to the other bit of reading I have been doing this week…

I volunteer as a lector at my parish. As

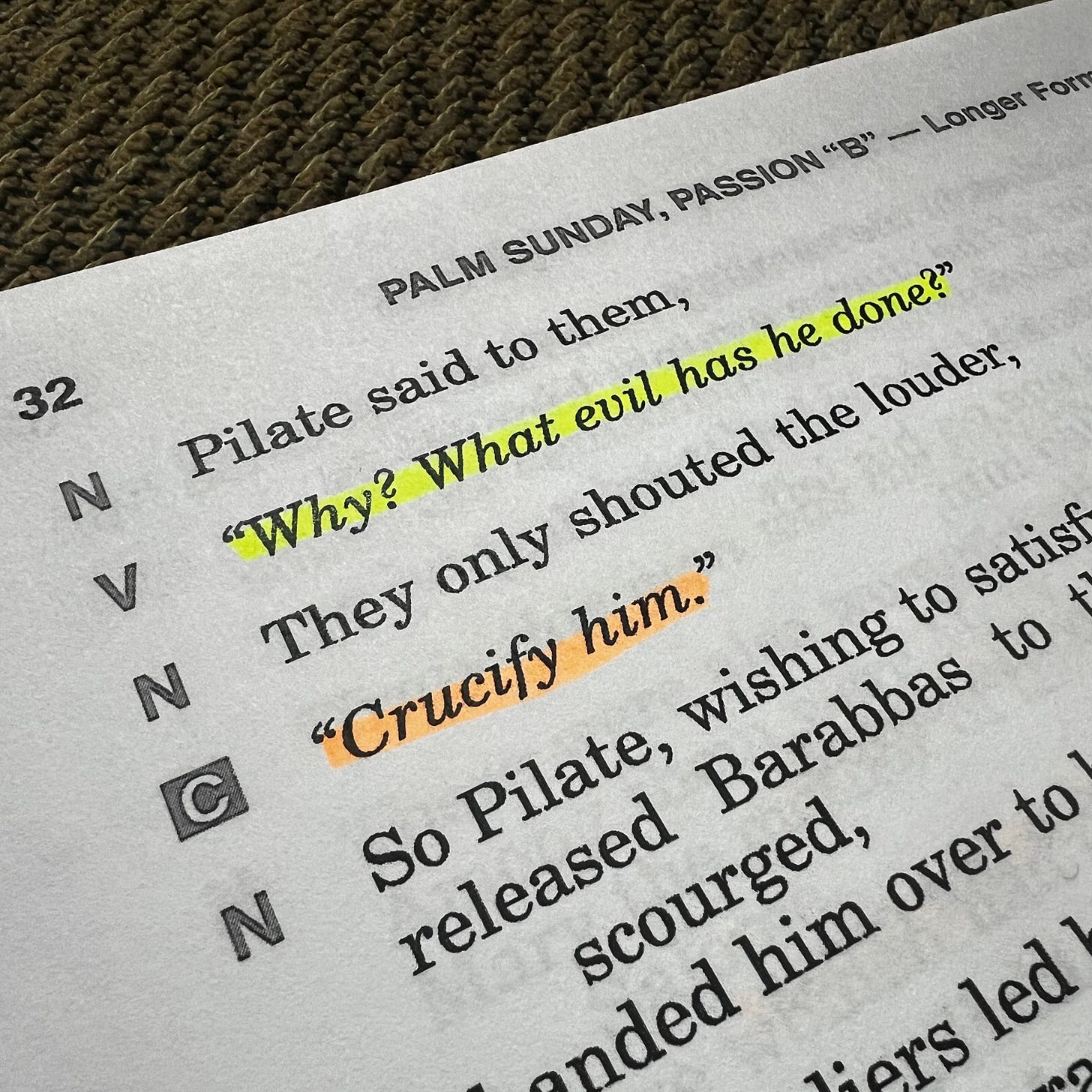

once said in an interview with Sam Fragosso, “It’s like doing a reading but with a much better author.”2Palm Sunday (or Passion Sunday as it was known until it was the two celebrations were combined after Vatican II) is the start of Holy Week for us, Catholics. This tradition dates back to 4th century Jerusalem and became quite elaborate in medieval times where the blessing of the palms started at one church and processed to another church for the singing of the liturgy by three deacons.3 Nowadays this Mass is celebrated with a long reading of the Gospel with the priest and two lectors. Tomorrow I am one of those lectors.

I take lectoring very serious so I prepare quite a bit. As I read through the Gospel I realized the weight of what I was being asked to say. My responsibilities include the voices of the crowd, the chief priests, the disciples, Peter who denies Jesus three times, Judas the betrayer, and Pilate.

My last line is the voice of the Centurion, who stood facing Jesus and saw him breathe his last…

“Truly this man was the Son of God!”

This begs the question:

Why do we made this Gospel at this particular Mass —Palm Sunday— a dramatic reading?

I wondered about this over the past few days, and then I read this post

published this morning.It touches on many issues, some of which are very personal to his experience with faith and family. I highly recommend this very genuine, and at times emotional, post.

But the part I want to highlight is what he wrote about Mircea Eliade’s book The Sacred And The Profane:

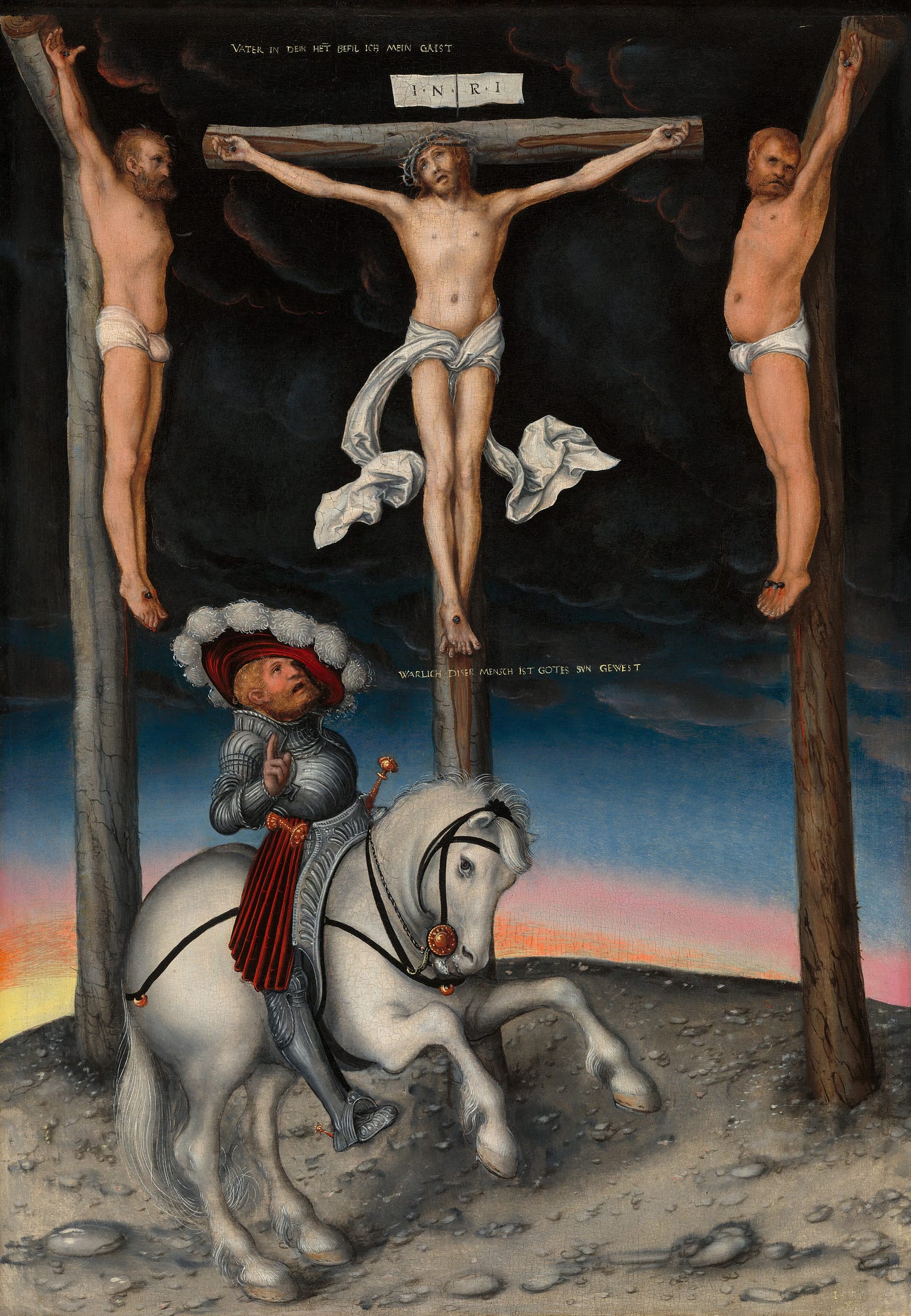

Eliade says that temples exist symbolically “at the center of the world” because they are where man establishes communication with the transcendent realm. It’s not that man can’t talk to God in other places and in other ways, but the temple is a special place set apart. The temple often represents a sacred mountain where the initial meeting with God happened. For traditional Christians, churches are a representation of Golgotha, and therefore “the pre-eminent ‘link’ between earth and heaven.” Obviously there are countless churches in the world, so understand that they all exist at the center of the world in a symbolic, mythic sense.

This jumped out at me because it is easy to see how the older, sacramental forms of Christianity conform to this global pattern. The death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth is the core of the religion, and is re-enacted every time there is a liturgy at the altar. The altar is Golgotha, which is part of Mount Moriah, on which the city of Jerusalem is built. When you take the sacramentality out of the religion, as many forms of Protestantism have, it wrecks the symbolism. How can a church that looks like a theatrical space do the symbolic work it is supposed to do? Does it matter? I think it surely must.

The idea that the altar is the place of sacrifice is a profound one, and I realized upon reading this quote from Dreher’s piece that how we say the Gospel this Sunday is not a piece of theater, although it may look like it at first blush. It is a “reenactment”—where we as a Church take part in the story of our own salvation. There is a difference. In theater, we are entertained. In reenacting, we relive.

Jesus was tortured, humiliated, and went willingly to his death.

He was treated as an enemy of the people.

Hostis publicus.

En folkefiende.

He was betrayed by Judas. Denied by Peter. And Pilate washed his hands of the whole affair after the crowd cried for His death.

The best stories show people who act in accordance to the truth, for the good of others, at the risk of their losing their own lives.

Miller’s adaptation of An Enemy of the People ends with Dr. Stockmann and his family trapped in their home with an angry mob outside.

Dr. Stockmann: But remember now, everybody. You are fighting for the truth, and that’s why you’re alone. And that makes you strong. We’re the strongest people in the world…

The crowd is heard angrily calling outside. Another rock comes through the window.

Dr. Stockmann:… and the strong must learn to be lonely!

The crowd noise gets louder. He walks upstage toward the windows as a wind rises and the curtains start to billow out toward him.

The Curtain Falls.

Yes, the curtain falls.

But the veil of the sanctuary is also torn. The temple is rebuilt. And the stone is rolled away from the mouth of the tomb.

Not just yet… for we have one more solemn week to go.

May the Lord bless you and keep you as we enter Holy Week. Thank you so much for reading this humble Substack. It truly means the world to me.

Pax et bomum.

Bonnie G. Smith, "A Doll's House", in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History, Vol. 2, p. 81, Oxford University Press

It is either this link: https://talkeasypod.com/george-saunders/ or this one: https://talkeasypod.com/george-saunders-returns/. Both are great. You should listen to them.

I wrote a paper in high school about Ibsen's A Doll House many many years ago. I don't remember much about what I wrote. It's nice to be reintroduced. A blessed holy week to you and your family.

Zina - great article. Love how you drew connections through all the different pieces and parts. Glad my small note could play a part in your week. Have a blessed Holy Week.