When I was a young girl, my father would take me on the Orange line from Oak Grove to Downtown Crossing so we could go to St. Anthony’s Shrine. He ferried me across the sea of people which, to a small girl like me, looked like a dark current of bodies of mostly legs and backsides. I saw sharply dressed men with their leather cases; women headed to Filene’s Basement, clutching their pocketbooks and smelling of l’eau de toilette; disheveled students and professors laden with papers, thoughts, and books; couples, standing, arms wrapped around each other; mothers with babies in arms, lulled by the rumble of cars; and people like me and my father. Sometimes we were crammed tight like fish in a can, and then the doors would slide apart. My father pulled me along by the hand as we were assailed by the smell of smoke and sweat, piss and oiled machines. He held my hand tight muttering, “I hate the smell of marijuana.” I decided right then and there that I hated it too.

We would ride the escalator to the sweet relief of light and air, emerging at the top of the stairs and making our way down the street. I’d hustle to keep up while thinking about Jordan Marsh blueberry muffins, hoping my dad would buy one for me if I was good at the shrine. I would often get one, but I don’t know if it was for being particularly good. I think he liked getting me a muffin because I get ridiculously happy when I eat baked goods. (I am still ridiculously happy when I eat baked goods.)

Jordan Marsh is long gone, having closed in 1996. If I want one of those blueberry muffins I have to make one myself.

My father is gone too.

On this day, nineteen years ago, my father passed away at home after a brief but excruciating battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 59 years old.

Tuesday, May 30, 2006, the day after Memorial Day weekend, my mother and sister were by his side as he took his final breaths while I was in Maryland with my husband and two young sons. My 10-month-old baby was very sick, and I had to take him to the doctor that day because he had been suffering from a serious infection. I waited in the examination room with my son whose cheeks were bleeding with mysterious sores. I felt all sorts of helplessness.

The pediatrician came in.

I blurted, “My father just died this morning.”

She paused. “Can I give you a hug?”

I must have looked like I needed it.

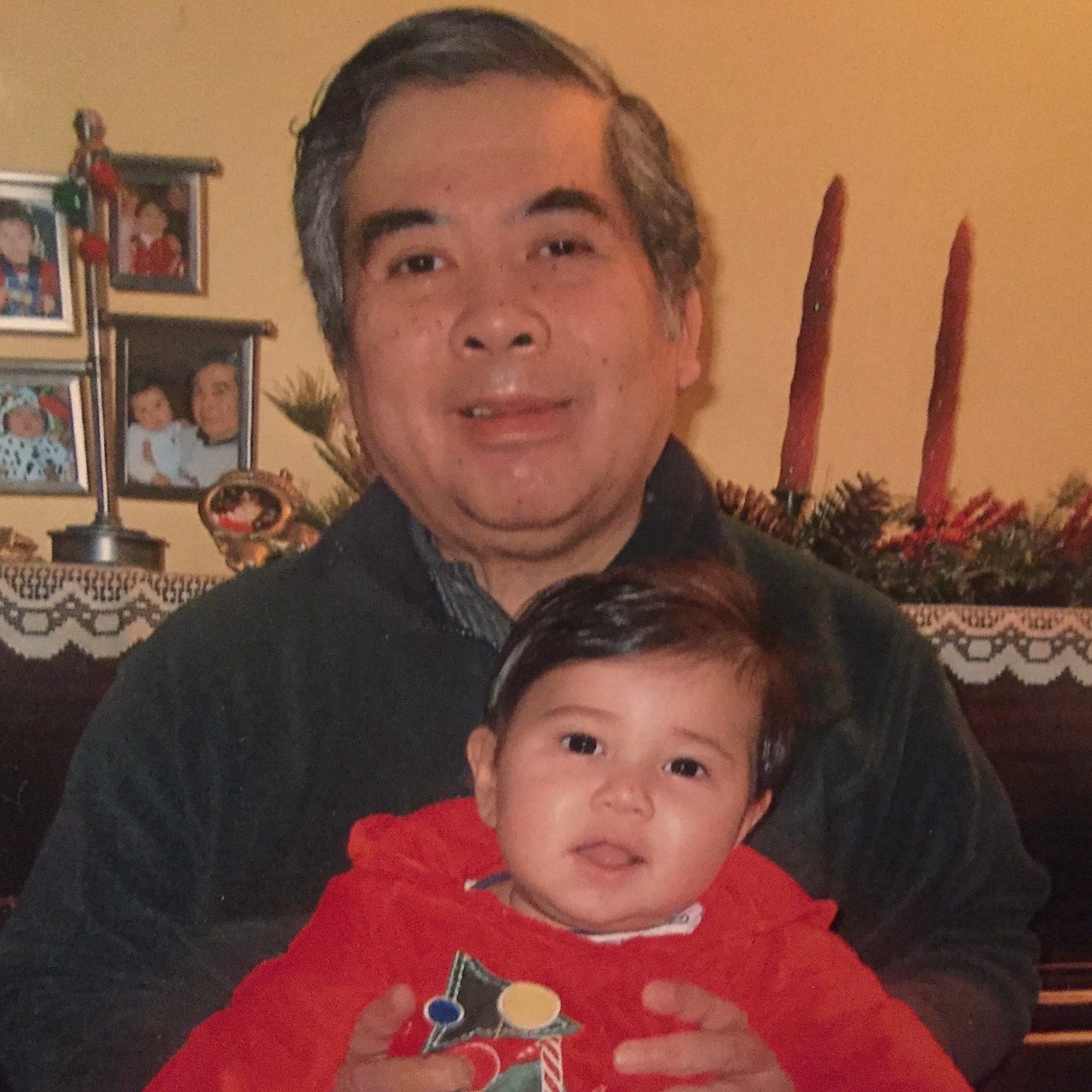

In this picture, my dad did not realize that he had a tumor in his pancreas that had already metastasized to his other organs. A couple of weeks later he was rushed to the hospital, and not long after that we were told that he was terminal.

The last time I saw my father he was resting in a casket. His skin was waxen and his color not his coloring at all. The beads on this rosary did not move between his fingers. When the wake ended the top of his casket was shut, a sound softer than a closing door.

My father was cremated, and his remains were interred in a cemetery just north of Boston. Since my mother had just finished radiation for her own cancer, my family decided to sell our house near Baltimore and relocate back to Massachusetts. My sister moved back from California. After having scattered in our young, independent adulthoods, the women of our family were reunited.

I started taking the T into the city again. However, I suffered from a strange phenomenon: I kept seeing my father riding the subway with me. Or rather I saw his likeness in some of the Asian men who were riding the train. His younger self, his older self. The Orange line, Red line, Green line. It didn’t matter.

wrote about reunion theory a while ago:In the months after a loved one's death, people, especially in western countries, people often report seeing their deceased loved ones in public settings or mistaking people for their deceased loved one. Some evolutionary psychologists suggest that the reason is that, when separated from a loved one, it is advantageous to be hyper-vigilant and monitor the environment for signs of the missing person. This is sometimes referred to as the “reunion theory,” which proposes that grief evolved in response not to death but to the prolonged separation or estrangement of a loved one.

This is consistent with the finding that people tend yearn for a reunion with the loved one for about 6 months, and then grow to accept the loss between 7-12 months.

Yesterday, I was a lector at the Mass celebrating the Ascension of the Lord. I read from Acts 1: 1-11 which described the apostles’ reaction to Jesus Christ being taken into heaven:

he was lifted up, and a cloud took him from their sight.

While they were looking intently at the sky as he was going,

suddenly two men dressed in white garments stood beside them.

They said, “Men of Galilee,

why are you standing there looking at the sky?

This Jesus who has been taken up from you into heaven

will return in the same way as you have seen him going into heaven.”

There are many details I forget about when it comes to the Bible, like the appearance of these mysterious two men saying that Jesus would come back as he had ascended.

I bet no one was thinking they would be waiting thousands of years.

I wonder if the apostles ever glanced at the heavens, waiting for a cloud to materialize into a white garment? A distant bird betraying the shape of a foot or a hand? We have minds that want to find patterns — to make sense of the world.

Our imaginations exploit our hopes.

Perhaps we are fools.

Are we fools?

Then I want to be a Holy Fool.

I remember taking the Red Line years ago, when my grief was fresh and particularly strong. There was a man at whom I could not stop staring. He had the same dark hair, flat nose, strong brow as my father.

I imagined mutual recognition. Some type of loss. The man looked at me with faint confusion that I fantasized as a memory stirred. Do I remind you of your daughter? Your wife? Your sister? Your mother as a woman-child seated for a sepia picture in the old country? Is there a river where she washed your clothes? Do you remember her hands wringing your shirt? Did you cry when you could not get to her in time, as you were propelled through the sky? You landed and you knew from the faces that met you on the tarmac that she was gone. Had you only looked out of your window you could have seen her ghost in the clouds. Her hands pressed against the windows. Her lips parted in her final breath—a goodbye.

Or am I a fool for Lethe

whose water I drank like wine?

The Charles is the River Styx.

We just crossed it on the Red Line.

The priest spoke the words of Luke 24: 50-53,

he led them out as far as Bethany,

raised his hands, and blessed them.

As he blessed them he parted from them

and was taken up to heaven.

They did him homage

and then returned to Jerusalem with great joy,

and they were continually in the temple praising God.

Eternal rest grant unto my father, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him. May his soul and the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

I lift my eyes to heaven.

I proclaim the Word of God.

I am in the temple praising.

Praise him. Praise his name.

Amen.

The way you weave memory, theology, philosophy, and poetry together is one of my favorite types of memoir. The longing and hope are both here. Thank you, Zina.

So moving and eloquent! Loss, as I know you know, challenges the writer. And yet we find a way as you have so beautifully done here, particularly for your father, his memory and his life and his way too early death.