The Beauty of Ambition

Can striving for greatness be virtuous? Visiting with classmates makes me question our individual and collective ambitions. Diving into a poem by James Matthew Wilson. BONUS: A list of poetry contests

“The same ambition can destroy or save,

And make a patriot as it makes a knave.”

― Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man

Not that long ago my grad school friend Christian Lingner and his wife Camila came up from Nashville to visit Boston. Another New England classmate, Alex, was able to meet us in Cambridge where we had a great time hopping around various shops for the day, having lunch and later getting coffee. Since our graduate program is conducted virtually, getting to know people can be a struggle. These in-person meet ups are a rare opportunity to connect.

I’ve met Christian and Camila in person just one other time, this past fall the at the Catholic Imagination/Center for Ethics & Culture Conference at Notre Dame. Christian presented a paper on the lyrics of John Prine, complete with a musical performance.1 I’ve set the video below to start at Christian’s talk, but the part I want to highlight is at the 35 minute mark.

After making light of the fact he has only 30 Spotify listeners,2 Christian says,

It seems like ambition leads inevitably to trading artistic integrity for the weighing of probabilities. And the weighing of probabilities leads inevitably to narrow and shallow outcomes. […] There’s a straight line from ambition to monotony, from avarice to the narrowness of sound and sentiment so characteristic of that premeditating professional: the marketer and his replicable product.

Garnering fame and fortune at the expense of authenticity and beauty is certainly an unattractive form of ambition. Christian describes musicians who create with the goal of material self-gratification — making music for the money (greed) and the admiration of fans (vanity). However, he describes John Prine as an artist who wrote music that he would not mind playing over and over, and that seems to be part of Christian’s own aspiration: to make music that is so good, true and beautiful that he could perform it happily for the rest of his life.

But is this the only definition of ambition? Isn’t trying to create the best art possible and be recognized for it another type of ambition? If one were to create soul-nourishing art for the advancement of our civilization, isn’t that a moral good?

Can striving for greatness be virtuous?

While searching for a particular quote by Robert Frost, I came across correspondence he wrote when he was just 20-years-old to an editor who had taken a look of his poems.3

You must spare my feelings when you come to read these others, for I haven’t the courage to be a disappointment to anyone. Do not think this artifice or excess of modesty, though, for to betray myself utterly, such as one am I that even in my failures I find all the promise I require to justify the astonishing magnitude of my ambition. [emphasis added]

In looking at some of the early poems myself, the quality falls under juvenilia, but as we all know Frost honed his craft and became one of our most beloved modern American poets. Isn’t our poetry landscape enriched by the fact that this young man pursued his ambitions? Yet at that young age, how could anyone be so certain of their potential? It is common for people to overestimate their abilities. Dunning-Kruger effect, anyone?

In a recent article in Plough, Justin Hawkins has an interesting take on Christian ambition:

Christians sometimes get queasy when talking about ambition. It can sound too much like the pride and presumption of the Greco-Roman world that Christianity sought to displace and transform. The Romans yearned for honor, grandeur, and glory, but Christ taught us to be humble. Christians strive to be faithful, not to be successful – so the argument goes. But there are good reasons for a Christian to keep the concept of success, provided it is rightly understood. In its most virtuous form, striving for success is the refusal to squander gifts, opportunities, and resources one has received and instead to build upon those endowments toward the attainment of some noble good. This form of nobility and human grandeur fits squarely within the Christian moral life, though Christians have often had to argue for this point against their detractors. [emphasis added]

The article is titled Christians Should Be Successful, and the subtitle proposes that a self-abasing person needs a virtue to complement humility which will prevent it from devolving into the mediocrity and smallness of soul. Hawkins makes a point that, rather than being a vice, ambition can be a healthy counterweight to a Christian tendency toward pusillanimity, an extreme self-abasement of one’s own gifts and dignity. I have known people who have suffered from this self-flagellating delusion — wrongly conflating humility with humiliation. Dunning-Kruger and pusillanimity sit on the unhealthy ends of the self-awareness scale.

However, a deeper explication of the term ambition is necessary because its meaning seems to sit on shifting sands. The more neutral and positive views of the word are a very modern invention. For much of its existence, ambition has had pejorative connotations since it steps from the Latin ambire, a verb meaning “to go around” which is what candidates for public office in ancient Rome had to do (i.e. canvassing for votes) in order to get elected. Thus ambition is associated with an inordinate desire for honor or power.

I’ve found one of the best modern examinations of a traditionally understood concept of ambition in this poem by James Matthew Wilson.4

“Ambition” by James Matthew Wilson

Halfway along in reading a new life

Of Dante, I’m still marveling at the man’s

Conviction he’s been set apart for greatness,

Though of its form

He’s still unsure. So far, in fact, he’s marred

Most that he’s tried and left the rest unfinished,

Promising nonetheless some lasting work

Not yet begun.

I bend still closer to the page, my mind

Halting before a pride it can’t quite fathom.

So it was with the climbing Dante, stopped,

Hunched down, to speak

With the famed illustrator he found crawling

Beneath a marble tablet on the route

To purification. How he lingered there,

Seeing his future.

He knew the punishment that he would suffer,

And suffer the more harshly for a vice

That strengthened him in flinty solitude and

Humiliation.

However true it may be that his poem

Would never have been written had he not

Sealed off his soul from all discouragements,

It’s still a failing.

After all, time will show the difference

Between the soldier of true courage and

The one whose brazen recklessness would lead

Men to their deaths.

The woman whom we think a connoisseur

Will soon enough be pegged as one that ooo’s

At everything which sounds like foreign chocolate

Or cellared wine.

Yes, there’s a reason that Aquinas said

That all ambition is a sin. We can’t,

While stiffened by that certitude it brings,

See the cause clearly.

For, in the genius plotting intricate rhymes

To execrate the avarice and envy

Of those who burned his home and cast him out

In wooded darkness,

Who passed a sentence on his children’s heads,

And, in the gangly dancer without rhythm,

The politician with a taste for fame,

It’s all the same.

It’s terrible that way, like power and beauty.

The mind can hover over its abyss,

Can hear the cataract roaring from below,

And see its force

Shaping the rough stone of the world about us.

But there’s no prior assurance; just the late

Judgement, once we’re past change and stooped to read

Our life’s spread book.

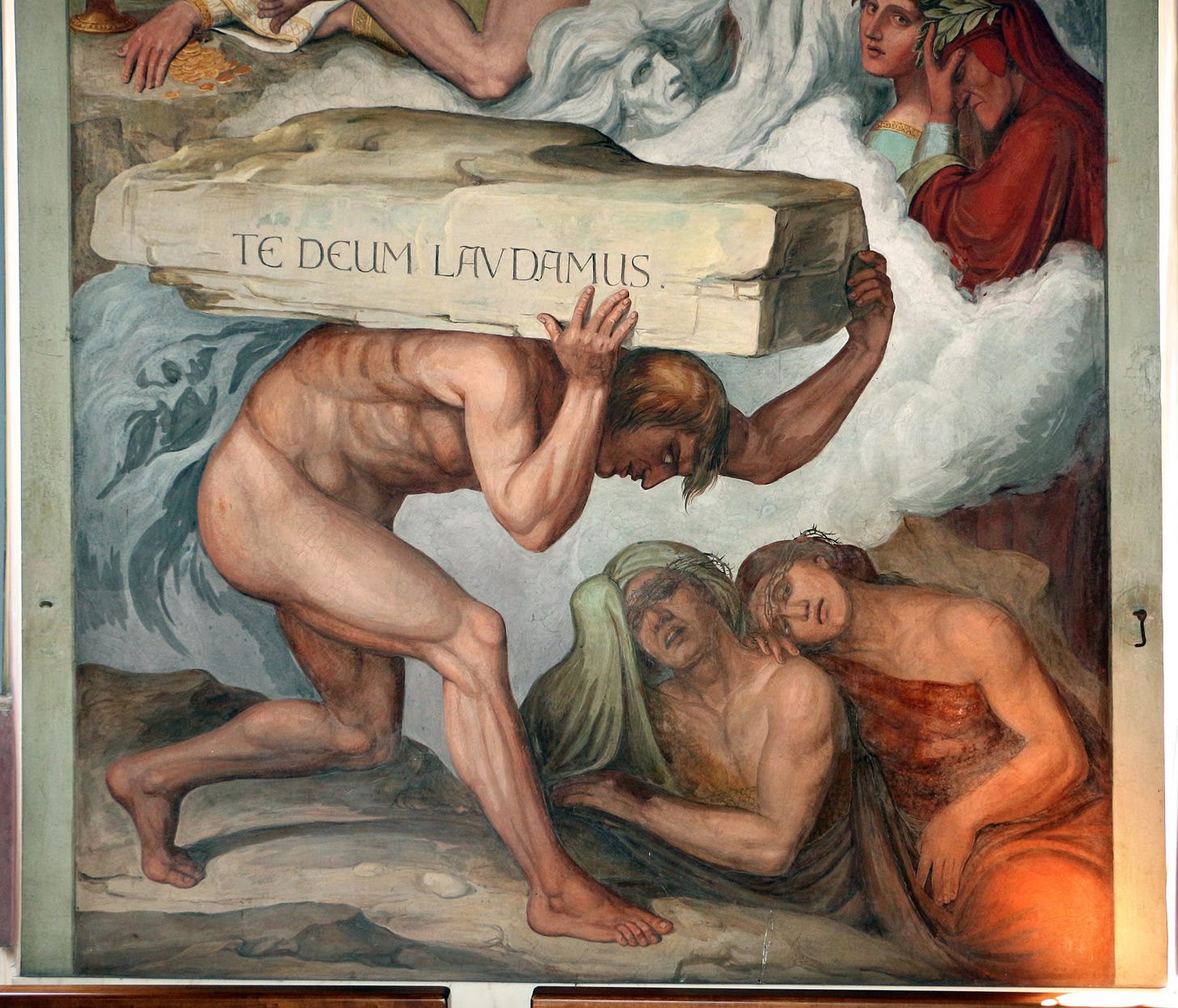

Printed with permission from the poet. Originally appeared in Hudson Review, Spring 2018.James Matthew Wilson knows a thing or two about Dante. He recently wrote a review in First Things about a new translation of The Divine Comedy by Jason M. Baxter. And one also sees his knowledge of Dante’s life inform the poem’s message about the dangers of ambition. Crafted in thirteen unrhymed iambic quatrains, “Ambition” employs pentameter for the first three lines of each stanza and dimeter for the fourth line, making each quatrain look like its own well-hewn marble block. From each stanza he chisels a meditation on art and worldly achievement that swings like a pendulum from the present day to the time of Dante and back again, the eyes of the speaker first looking at a page of the great poet’s life and then coming to rest on the book of his own judgement.

We enter the poem with the speaker considering Dante’s conviction that “he’s been set apart for greatness” — not unlike the young Robert Frost whom I mentioned earlier. Nothing of brilliance has yet been produced, however, the reader knows that Dante will achieve something of lasting fame. How could he have known? This is a question the speaker asks in line 10 with “a pride it can’t quite fathom” even as Dante meets with Oderisi of Gubbio in Purgatorio, the great illustrator beneath a marble tablet, punished for his pride in artistic achievements. It is precisely this scene, that makes this poem utterly mind bending in its meta-ness. Here is Dante who has written the character of Dante confronted with a Dante-like, prideful artist. Dante “knew the punishment that he would suffer, / And suffer the more harshly” and yet he proceeded in his writing. It is this stanza, with a stunner of a last line, that brings the reader out of Dante’s life and into the thorny issue of ambition:

However true it may be that his poem

Would never have been written had he not

Sealed off his soul from all discouragements,

It’s still a failing.

What is the failing that the speaker speaks of? The poem, The Divine Comedy? No. In the grand scheme of things, art is a worldly endeavor, but the soul is immortal and is of the utmost importance. Therefore, it is in stanza 9 that things are laid bare with the word that our current culture never wants to acknowledge: sin.

Yes, there’s a reason that Aquinas said

That all ambition is a sin. We can’t,

While stiffened by that certitude it brings,

See the cause clearly.

We can’t see the cause clearly because it is in our human natures to not be able to. It is an unfortunately feature of our fallenness. Ambition is the certitude, the lie we tell ourselves for we can never be completely certain, on the way to our desires being realized or denied. Worldly success is often used to justify ambition, but that does not mean that ambition is ever justified. As Aquinas said, all ambition is a sin for the harm it does to the soul. And the stanza that follows uses the revealing word, execrate, which means to loathe. The worst form of ambition is one exercised out of loathing of others and stems from the deadly sin of Pride.

Other than Dante, the other examples of sinfully ambitious people include the foolhardy soldier, the poseur connoisseur, the gangly dancer, and the vainglorious politician. They are characterized as people who think more of themselves than is justified. Yet, “time will show the difference” between the courageous and the reckless. This line tips a hand toward the possibility of achieving honors through some virtue.

The last two stanzas seal the poem in a Book of Revelation flavor of existential terror:

It’s terrible that way, like power and beauty.

The mind can cover over its abyss,

Can hear the cataract roaring from below,

And see its force

.

Shaping the rough stone of the world about us.

But there’s no prior assurance; just the late

Judgement, once we’re past change and stooped to read

Our life’s spread book.

Ambition, power and beauty in and of themselves are actually neutral forces; however, they are often abused, becoming the pathways of soul-corrupting Sins: Pride, Envy, Wrath, Sloth, Greed, Gluttony and Lust. The power of human nature takes shape in the form of the cataract, a brilliant word choice as both a thundering waterfall but also as a condition that obscures vision. Ambition blinds us to our true motivations. In the end, we will be judged after we have created our art, and since complete self-awareness is impossible we will not know if we did things for the right reasons until it is too late. The path to the Inferno is paved with good intentions.

The last two lines bring us back to the “meta” aspect of this poem. Although the speaker of any poem is often just a persona created by the poet, in this case it is easy to see the speaker as James Matthew Wilson. Honestly, how does a man read an article that proclaims him “The Finest Poet-Philosopher of the Modern Age”? What happens to the ego when

goes on record saying, “James Matthew Wilson is the most conspicuously talented young poet-critic in American Catholic letters.” Let me now propose this hall of mirrors reading of “Ambition”: As a student of James Matthew Wilson, I am an ambitious poet examining the verse of an ambitious poet who is reading about the life of a ambitious poet who has written himself into his epic poem as a pilgrim encountering an artist who is condemned to an excruciating punishment consistent with his sin of ambition. If that isn’t meta then I don’t know what is. The poem begins in the first person singular but then makes the turn at the end to “us” and “our life’s spread book” — making a single reader’s contemplation into a collective caution for all readers of this poem. The intellect and imagination of his poetry combined with the precision of his versecraft are the reasons why Dr. Wilson is lauded as much as he is.However, color me unconvinced as to the outright sinfulness of ambition. It is due to the word “execrate” in the tenth stanza. Ambition can remain neutral striving until it is corrupted by loathing, hatred, or a feeling of entitlement over others. The problem is that keeping one’s ambition from becoming untainted by jealousy and disordered pride is extremely difficult. But I think one can be humble and yet ambitious. It is the job of an artist to know the beauty and excellence that is possible and to study one’s craft so that the gap between one’s abilities and one’s vision are closed to the greatest extent possible.

One of my classmates, Maura Harrison, is one of those people who I think of as an ambitious and visionary person. She is a writer, photographer, and fabric artist. She created An Illustrated Comedy, a special collection of 100 collages, one for each Canto of Dante’s Divine Comedy. However, her recently published poem in The Society of Classical Poets, “Emergent Occasions” is one that displays something I’ve seen from her time and time again: artistic ambition. Her note for this poem speaks to the high bar that has for her writing:

This poem uses the form found in Donne’s “The Relic,” (4a, 4a, 4b, 4b, 3c, 5d, 3d, 4c, 5e, 5e, 5e). The content is responding to Donne’s essay titled, “Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions.” It has a stanza for meditation, discourse, and prayer (to match the structure of Donne’s essay).

“Emergent Occasions” by Maura H. Harrison “And even angels, whose home is heaven, and who are winged too, yet had a ladder to go to heaven by steps.” —John Donne, Meditation II, Emergent Occasions

Affliction is a sea, a sink,

A place that begs the soul to think.

As treasure, sick-bed souvenirs,

Woe wets our ashes, gilds our tears.

Grave sickness digs our earth,

Plants death—sends soil and heaven falling together

Tangling rise and tether.

Most nights we copy death, measuring our worth

By oilless lamps, sleeping complacently.

But with the embers of disease, we see

The circumstance of our emergency. Mankind, all earth and dust, is fixed

To misery. We’re merged and mixed

And gathered, isles to continent,

And kept, so centered, on ascent.

Do dusty pilgrim feet

Remind us that we’re walking bags of water,

Woe-wrung and carried farther

West as we quest for East? Toiling, we meet

Our forma, earthen clay, dirt dipped in sea

And muddied step by step, dried by degree,

But pliable with this sweeping misery. Come mortal moment, shake my soul,

Come up and out and rise, come toll

My bells, reverberate my time

With vigor, spur me forth to climb.

As even angels, winged,

Have ladders, going step by step to heaven,

Help me, enlightened leaven,

To lift my gaze. Restore my sight and bring

Me, wingless, to the highest rung to see

Night’s mineral fleck, soul’s osseous esprit

Reflecting heaven’s light, stars on the sea.Printed with permission from the poet. Originally appeared in The Society of Classical Poets on 1/11/2025.

When I read a poem like this, it delights my mind, bringing me closer to some type of light I can’t yet describe. Great works will do this to me, and it inspires me to reach that same high bar for the sheer exhilaration of having achieved something. I would say that Maura’s work is often ambitious.

Being at this graduate program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston with professors like James Matthew Wilson and Ryan Wilson has made me rethink my own capabilities. It has made me expect more of my writing, showed me possibilities and unlocked doors to my imagination that I never knew could be opened. I’ve been blessed with supportive and talented peers like Christian Lingner, Alexander Pease, Maura Harrison,

, , , , , , and many more.And finally, if I had no ambition I would have never started a Substack. I began this newsletter two years ago this month having written very little, and I had no published work in any online or print journal. I had nothing but the desire to write and the belief that I could write something that someone would want to read — and perhaps even pay for.

A lot of beauty has been created with the fire of ambition. As long as we make art from wanting for the good of others, as long as we are rightly oriented toward truth and goodness, our idealistic striving can be a moral endeavor. God gave us gifts that we should not squander.

Now I leave you, my friends, with opportunities on which to focus your own ambitions. These contests are for single poems, not chapbooks or collections. For the ones where I know the judges, I have listed their names. They are in order of deadline so act fast on the first one!

The 47th Nimrod Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry

Deadline: January 31, 2025. Prize: $2,000 and publication, Second place $1,000 and publication. Entry Fee: $25. Click HERE for details.

Bellingham Review’s The 49th Parallel Award for Poetry

Deadline: March 15, 2025 (opens February 1). Prize: three $1000 prizes each and publication in Bellingham Review. Entry Fee: $15. Judge: Gabrielle Bates. Click HERE for details.

15th Annual Frost Farm Prize for Metrical Poetry

Deadline: March 31, 2025. Prize: $1,000 and an invitation, with honorarium, to read at the Hyla Brook Reading Series, August 15, 2025, at the Robert Frost Farm in Derry, New Hampshire. Judge: Maryann Corbett. Click HERE for details.

Indiana Review Poetry Prize

Deadline: March 31, 2025 (opens February 1). Prize: $1000. Entry Fee: $20, which includes a journal subscription. Click HERE for details.

Catholic Literary Arts 2025 Sacred Poetry Contest

Deadline: March 31, 2025. Prize: First place $250, Second place $200, Third place $150. Entry fee: $25. Judge: Sally Read. Click HERE for details.

2025 Prime Number Magazine Awards for Poetry

Deadline: March 31, 2025. Prize: $1000, and 2 runners up $250. Entry fee: $15. Judge: Molly Rice. Click HERE for details.

Wergle Flomp Humor Poetry Contest

Deadline: April 1, 2025. Cash Prize: $2,000, a gift certificate for a two-year membership to the literary database Duotrope, and publication on the Winning Writers website. Entry Fee: $0. Click HERE for details.5

Plough Quarterly’s Rhina Espaillat Poetry Award

Deadline: April 30, 2025. Prize: $2000 first prize, $250 for two runners up. Entry fee: $7 (waived for subscribers). Judge: Jane Clark Scharl. Click HERE for details.

Beloit Poetry Journal’s Adrienne Rich Award for Poetry

Deadline: April 30, 2025. Prize: $1,500, Entry Fee: $15. Judge: Marilyn Chin. Click HERE for details.

One of my other graduate school mates Eric Cyr was the first speaker. And Colin Cutler was the third speaker. It’s a great presentation, but I have set the video to start at Christian’s talk.

In case you are interested, Christian actually released a song on Spotify this week!

From The Robert Frost Reader: Poetry and Prose, edited by Edward Connery Lathem and Lawrance Thompson. This quote comes from a 1894 letter written by young Frost to Susan Hayes Ward, the literary editor of The Independent, where his poem “My Butterfly” was first published.

I write this at my great peril since he still grades my work for class. I approach this with great humility, with great disregard for my own ambitions.

Thanks for this intriguing reflection, Zina. There is ambition but also gratitude in Dante's depiction of Virgil. I wonder if one warning sign is when rivalry towards one's artistic peers and mentors trumps gratitude. It seems then that "healthy" ambition has given way to envy and pride.

As an honest minor writer and 99 percent atheist, I aspire to be my best writer self. This ambition seems honorable to me. It gets complicated by the humiliating stab of envy toward writers who are getting more ink and selling more books—the “sots and thralls,”

as Hopkins called them. I am at peace with myself when I focus on where I am on my path, as opposed to where others might be.