Mrs. Jack’s Palace of Impermanence

On the centenary of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s death: a crime scene, a museum tour, a mini-memoir, a bit of biography, and a brief look at four books.

What I’m about to tell you is not so much an essay but an informational story—part book review and part biography with a touch of memoir and real-life mystery. And it concludes with a revelation of sorts.

This is for Wendy, Suzanne, Shannon and Leah.

But this is also for whoever, by providence, finds this post.

Back in 1988…

When I was a freshman at Pope John XXIII High School, I had such a weird schedule that the only elective that was available to me was art which to my knowledge was something you did in your spare time when you didn’t want to think. I didn’t want to take it because I didn’t think it was going to help me get into a good school. However, after the first year I realized that it was also going to be an easy “A” every year, which wasn’t necessarily a bad thing for my GPA. It also played to my strengths of having good fine motor skills and hand-eye coordination. My teachers were the most generous and supportive adults I had ever encountered, and my classmates were the most fun-loving and relaxed people. In terms of rigor, we had to not just create art but study art history. I was very preoccupied in my classes, and I think it made me a better observer—thus a better writer.

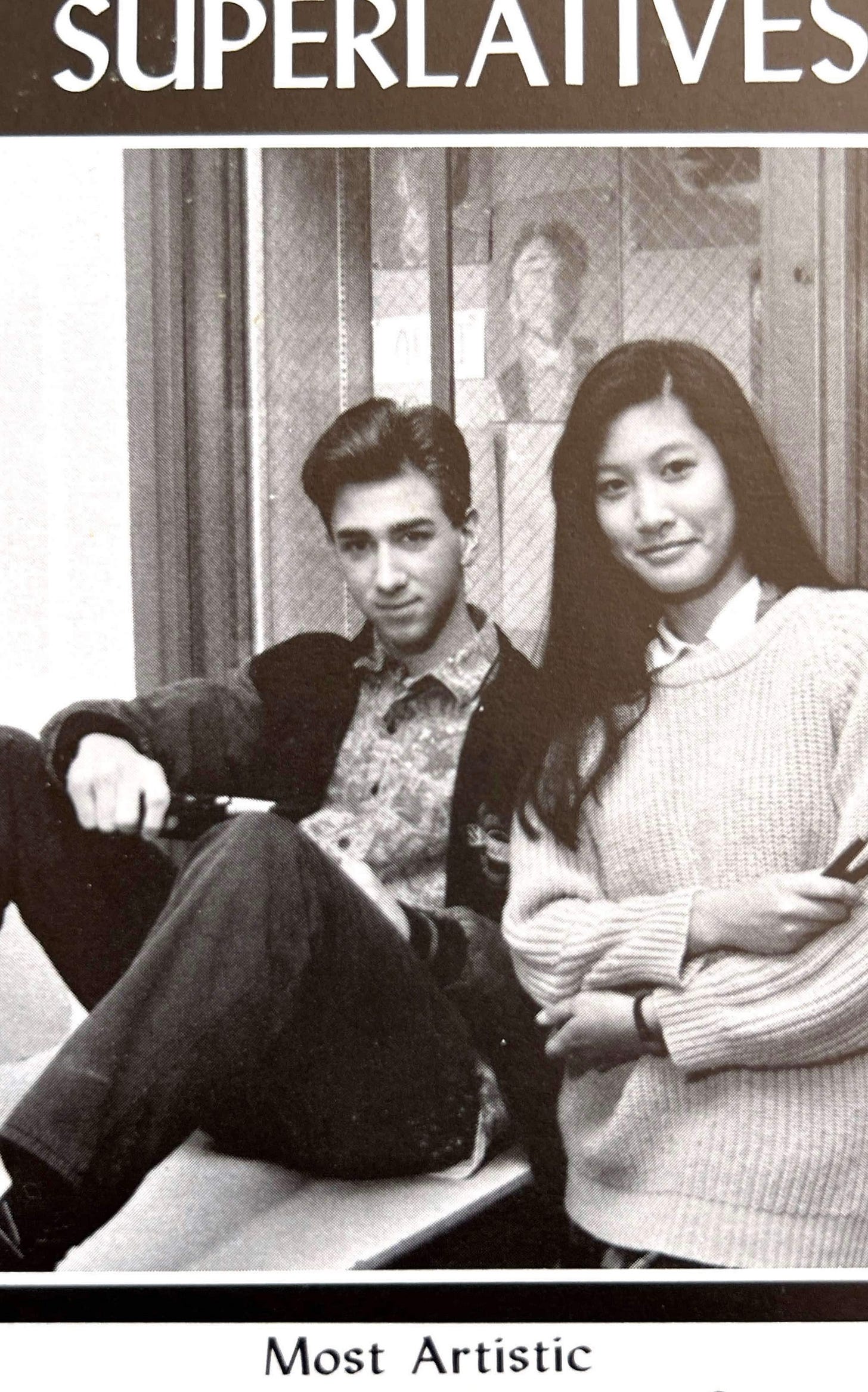

Although I started high school with a contempt for Art, I ended up choosing it as my elective every year, and by my senior year I ended up sharing this honor in the yearbook:

Some of our assignments required us to visit museums and copy art in our sketchbooks to bring back to school. Our student status gave us free or discounted admission to museums and cheap transportation on the T. Of all the places I visited, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum was by far my favorite.1

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

As a teenager I remember entering the building for the first time and being struck by the tension created by light and darkness. The rooms were dim, but the courtyard was brilliant and perpetually verdant.

There are no plaques to describe the art, but everything makes sense where it is. All objects were arranged carefully, according to the mind of an eccentric and wealthy socialite who, upon her death, required that nothing be moved from where she placed it or else everything would be sold and the proceeds sent to Harvard.

I was a high school art student from 1988 until 1992. Right in the middle of my studies, in 1990, one of the most notorious art thefts in history was committed at the Gardner.2 When you are young and you love a place, an event like this violates your sense justice. No great care was taken in robbing the museum. Paintings were cut out of their golden frames. It was an act of violence perpetrated on Beauty.

Most people visit museums to see the art curated within them. Since the robbery, the Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum is distinct in how many guests come to see what isn’t there. The Heist is so much a part of the museum’s identity that its website has an audio tour that allows visitors to retrace the steps of the thieves. It starts where the most valuable of the 13 pieces of stolen art were once displayed…

The Dutch Room

On Wednesday, July 10, 2024, I was making my first visit to the Gardner Museum since high school. After visiting the rooms of the first floor I made my way up to the Dutch Room which once held, among other pieces of stolen art, Rembrandt Van Rijn’s Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee.

It was in front of this empty frame that I met Wendy, Suzanne, Shannon and Leah, four friends (two of whom from Canada) who were touring the Gardner. They had questions about the theft, and I happened to have some answers because I read several books before I came to the Museum, and I had memories from the time I was in high school.

Here is the art that should have been in the largest frame…

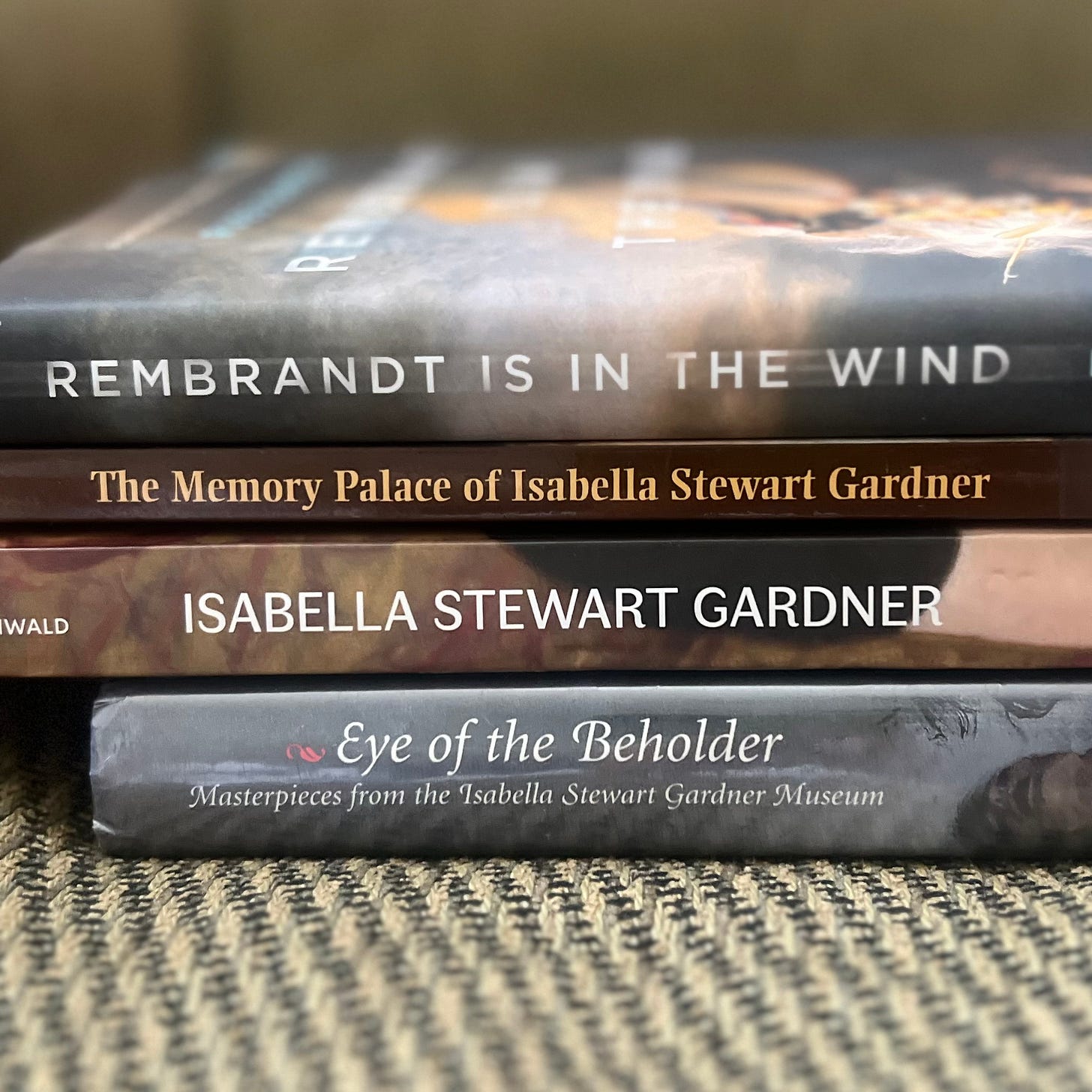

It was this painting—or rather its absence—that brought me to the museum. Upon the recommendation of a friend, I read Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art Through the Eyes of Faith by Russ Ramsey which gets its title from the famous painting.

I also ended up reading other books as well.

Rembrandt Is in the Wind: Learning to Love Art Through the Eyes of Faith by Russ Ramsey (2022). This is a book that deserves more than the brief blurb I can write in this post, but overall Russ Ramsey is very successful at orienting art and beauty with a Christian perspective of aesthetics using the lives of several famous artists: Michelangelo to Vincent van Gogh to Edward Hopper. The chapter on the stolen Rembrandt reads like a crime thriller. Please note that there is one chapter in particular that is very flawed. It has nothing to do with the Gardner so I will not go into that here, but I wanted to warn you in case you thought I was giving an unqualified recommendation. The book is, however, quite good for those who are new to art history and are friendly toward a Christian mindset.

The Memory Palace of Isabella Stewart Gardner by Patricia Vigderman (2007). I had great hopes for this book. The concept of using the rooms and the art they contain as a “memory palace” for remembering Isabella’s life was very compelling. Alas, the entries did not progress logically in the museum space, and the writing itself lacked focus and too often strayed into personal meditation that was too specific to the author and not connecting with this reader.

Isabella Stewart Gardner: A Life by Nathaniel Silver and Diana Seave Greenwald (2022). Written by the curator and assistant curator of the collection respectively, this is a well-tempered and thorough biography of Mrs. Gardner that never tips into hagiography or sensationalism, as some books on Isabella Gardner seem to. It also spoke about the spaces in the museum in a way that I was hoping that Vigderman’s book would, and in a way it was more successful as a “memory palace” aid.

Eye of the Beholder: Masterpieces from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum edited by Alan Chong, Richard Ligner, and Carl Zahn (2003). This is a large format book with great prints and thorough descriptions. If you are serious about looking at the art in more depth, I recommend finding a copy of this (I borrowed it from the library). Unfortunately, I believe this is out of print.

The Gothic Room

I took these new found friends all around the museum, including the Gothic Room. The museum holds several notable portraits of Isabella Gardener. The most stunning is the large one on display here: John Singer Sargent’s Portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner (1888).

The other two portraits I find fascinating are Anders Zorn’s Isabella Stewart Gardner in Venice (1894) in the Short Gallery and Sargent’s watercolor Mrs. Gardner in White (1922), which was painted two years before Isabella’s death. A reproduction is displayed in the MacKnight Room.

The Chapels

As per Isabella Stewart Gardner’s wishes, every April 14 a religious service is celebrated in honor of her birthday in the chapel on the third floor of the museum. Mrs. Gardner was very religious in a Latin/high Anglican sense. Although there are pieces of art in the building that reflect other religions, museum is dominated with Christian scenes and stories. Images of the infant Christ breastfeeding from Mary are quite prominent. For example, you can see a statue of the nursing Madonna and Child in the Spanish Chapel off of the Spanish Cloister.

The Little Salon and Archives

In the archives (not on display) there is a rare candid photograph of young Isabella holding her only child, John Lowell Gardner, III, whom she affectionately called “Jackie.” This is probably the most joyful image of the socialite ever captured. Jackie died of pneumonia not long after this photo was taken, when he was three months shy of his second birthday. Letters suggest that Isabella later suffered a miscarriage. After Jackie, Isabella and Jack were never able to have children of their own.

After the death of Jackie, Isabella fell into a depression, and it was suggested that Jack take her to Europe. This trip seemed to be the start of the Gardners collection of fine art in earnest. It was as if the cure to Isabella’s grief was the pursuit of beauty.

Echoes of Isabella’s sorrow ring through her collection. There is a cabinet in the Little Salon that displays a watercolor of John “Jackie” Lowell Gardner, III. Below the picture are small photographs of young Isabella Stewart Gardner, her nephew Joseph Peabody Gardner, Jr. (who died by suicide as a young man), and Isabella’s husband John “Jack” Lowell Gardner, Jr.

Joseph and his brothers were raised by Isabella and Jack after Jack’s sister-in-law and brother passed away when the children were young.

When Jack died, Isabella moved swiftly with their plans to build the museum they had envisioned: Fenway Court. After the completion of the building, Isabella worked to bring their art collection into the museum. She sold her other Boston properties which reduced her staff and expenses, and she moved into the top fourth floor apartments in the museum.

The Courtyard

The museum seems to exude a feminine energy, emanating from the very heart of the building: the Courtyard. From the mosaic of Medusa on the ground and the statues of Persephone and Diana, the lush, year-round garden speaks to the power of fertility and female power.

Interestingly, after her death, a plaque was taken off the building to reveal the full name of the museum underneath: The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in the Fenway MDCCCC. Not the John and Isabella Gardner Museum. As someone who was called Mrs. Jack during her life, it seemed like she was determined establish this place as a reflection of her own personhood.

She placed artwork and artifact in every room to be in conversation with each other, and yet it is more than that. It is as if she wanted the art to communicate something of herself to everyone who visited the museum, even after her death.

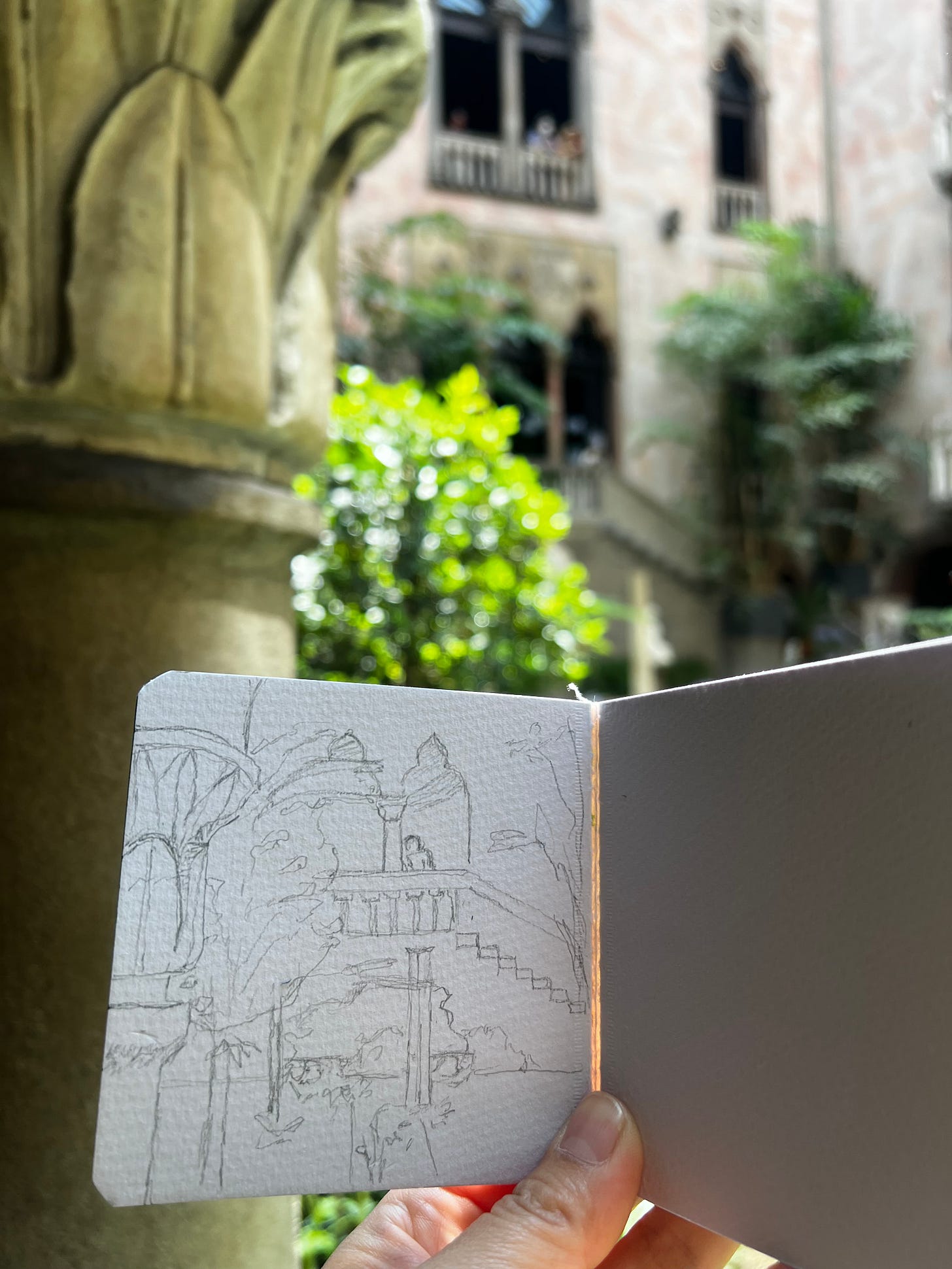

My way of communicating back is to try to make art again, which I have not done in many years. I’m not as good as I used to be, but I am determined to come back more frequently and sketch more. I can only get better with practice.

July 17, 2024 — The Centenary

I am writing this on July 17, 2024, the 100th anniversary of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s death. Coincidentally, it is also the birthday of my parents who were born on the same exact day in the Philippines. My mother is alive and well, but my father, Nicolas, passed away 18 years ago. Today I went with my mother to visit my father’s grave.

It is also a week since my visit to the Gardner Museum—when I gave a tour to four strangers whom I met in front of an empty gilded frame. The funny thing is that I was never supposed to be in Massachusetts that day. That whole week my family was supposed to be in Vermont on vacation, but due to unforeseen circumstances we ended up canceling the trip. Perhaps the inconvenient turn of events was providential, for not long after settling back home I found out that a friend suddenly died and being home meant I could attend her funeral. Her children went to elementary school with my children. She was only 51-years-old.

Of course, I never told Wendy, Suzanne, Shannon and Leah that one of the reasons why I was more than happy to walk them around the museum was because it reminded me of being with those I love, particularly those who has passed on. Just a few hours later that day I would be meeting friends at church to attend Laurie’s wake.

It is appropriate that this chance meeting would happen in a palace built with a woman’s grief. The museum is, in a way, a living memorial to what she loved most.

Isabella wanted everything as she left it, but one evening in 1990 showed that no matter what provisions we put in place we cannot keep everything as we desire. Life is so fleeting. Change is the only constant.

Rest eternal grant unto Isabella, Jackie, Jack, Nicolas, Laurie, and all those who have gone before us, O Lord. And let light perpetual shine upon them. May they rest in peace.

Amen.

Isabella Stewart Gardner

April 14, 1840 – July 17, 1924

American art collector, philanthropist, patron of the arts, and founder of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is free for visitors aged 17 and younger and anyone named “Isabella”.

Google’s Arts & Culture has a very engaging site to explore as well.

A great piece. During the pandemic the streaming services were rife with documentaries about art forgers and thieves, for some reason, but they were great distractions. One was about the Gardner museum (This Is a Robbery: The World’s Biggest Art Heist). Fascinating. Not so much the robbery itself, as that seems in hindsight almost inevitable considering the lax security, but the odd investigation that followed, with its many theories about who committed the theft and what happened to the art.

I just happened to read Chandler’s The High Window this week, which involves the theft of an 18th century coin so rare it couldn’t be sold openly, like the stolen paintings. In the absence of a real-life Philip Marlowe, the best that can be hoped, I suppose, is that some of the paintings ended up in a shady private collection and one day will be recovered.

I recently bought Rembrandt is in the Wind after seeing it recommended several times over the last few years, including a friend who passed away just a couple months ago. Would love to hear your thoughts/corrections on the problematic chapter!