Loving the Stranger

On xenia as a poetic necessity. In memory of Danielle Legros Georges (February 14, 1964–February 11, 2025), 2nd poet laureate of Boston.

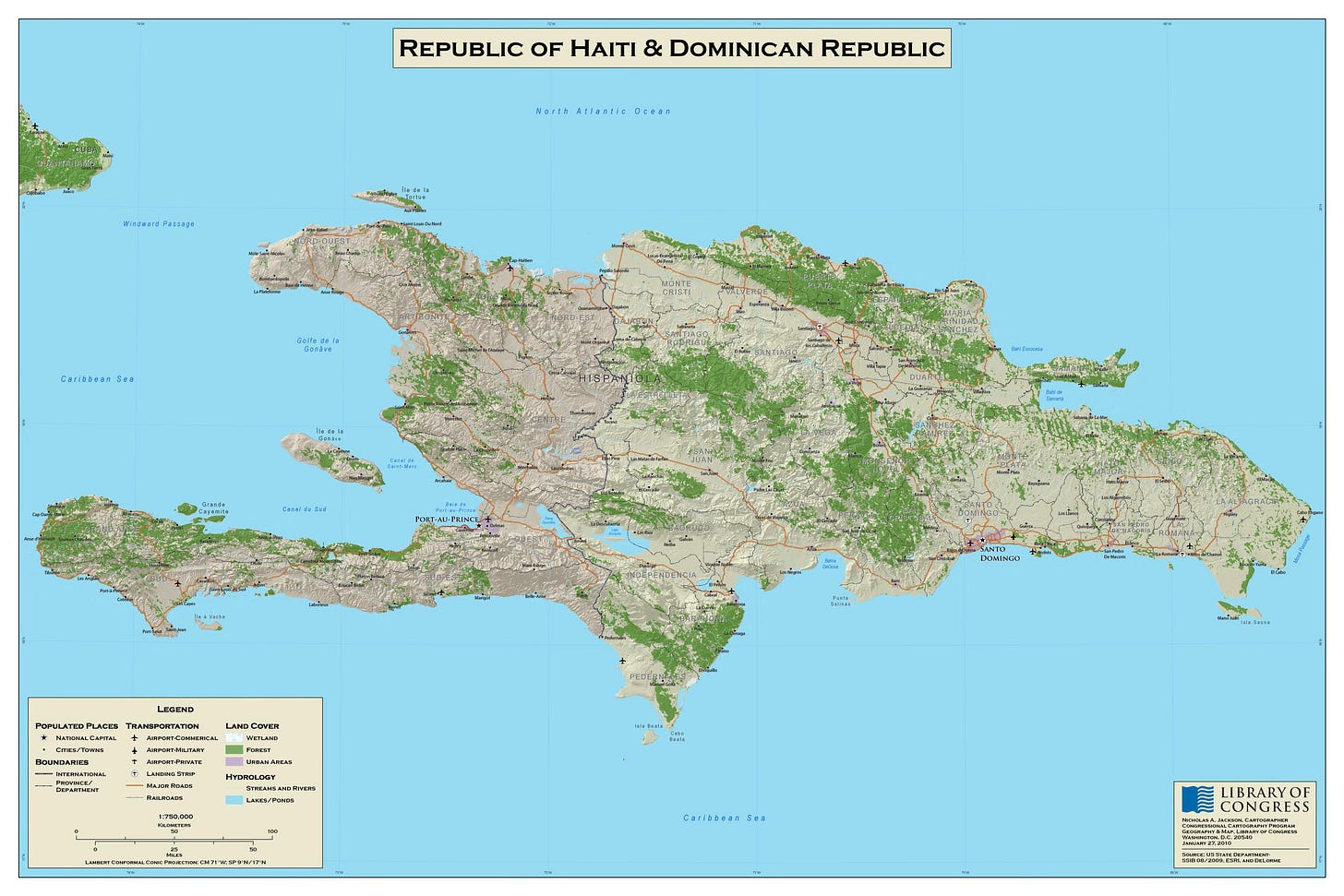

On September 14, 2024, I was sitting in the audience as Danielle Legros Georges read her poetry at the Newburyport Library at the invitation of the Powow River Poets. She was introduced by Rhina Espaillat who noted that she and Danielle were born on the same island but in two separate countries, speaking two different languages. Georges immigrated to the United States as a child from Haiti and Espaillat from the Dominican Republic.

Given Espaillat’s introduction to Georges, the poem “A Stateless Poem”1 stands out in my memory. You may find it here on The Johannesburg Review of Books which notes at the end of the post:

“A Stateless Poem” addresses a September 2013 ruling by the Dominican Republic Constitutional Court that stripped citizenship of Dominican-born persons without a Dominican parent, going back to 1929. The majority of persons affected are Dominicans of Haitian descent.

The poem consists of couplet stanzas, with one exception, and moves through a series of seven questions. There are sentences and fragments that are punctuated by periods, however, they seem more like branches from the main interrogation rather than independent thoughts in and of themselves.

The third stanza asks “what are you? Who are you? And who / am I […]” And the rhythm of the language is reinforced by anaphora, the repetition of the words: If… Who… With…

The poem turns on a single line of two questions: Who native? Who other? The speaker first addresses “you” — the other — and then challenges herself in “I” and finally asks the collective “we” — those who avoided statelessness by “accident of blameless birth”:

“Who are we to be / so lucky?”

If you look at the map, what is the difference between us and them? Haitian and Dominican? The difference is political, man-made — an exertion of power. The line break of that last sentence is dictated by human decision. It is purposeful, drawing the eye to a rhyme, to the fact that this is a question being asked by a poet, who reigns as sovereign over her work. The poem is about power: who has rights and who doesn’t, and the ethical necessity of questioning that power by those who have benefited from it.

The Haitian and the Dominican are the same islanders. Danielle Legros Georges and Rhina Espaillat, of two languages and two republics, are sisters of geography — and vocation. Teachers, poets, and translators.

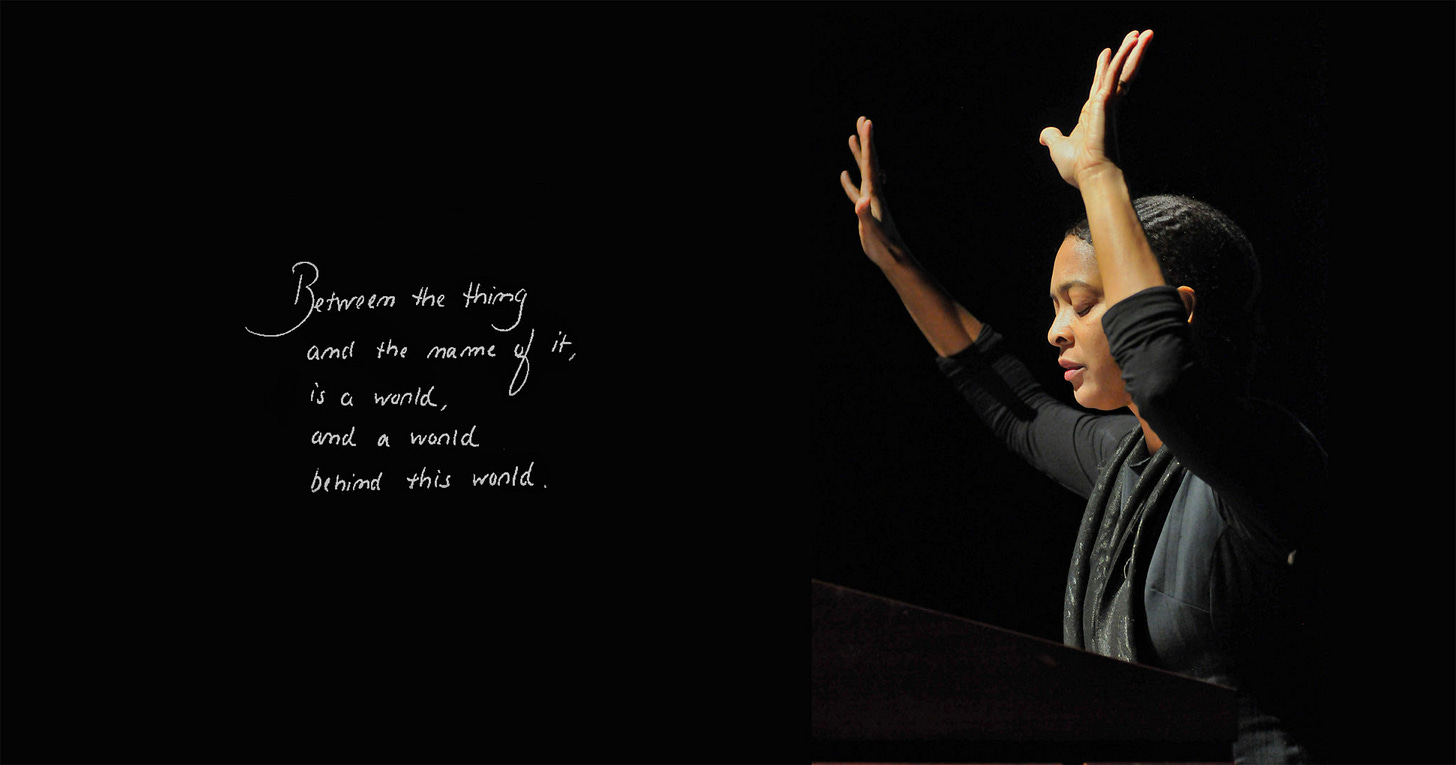

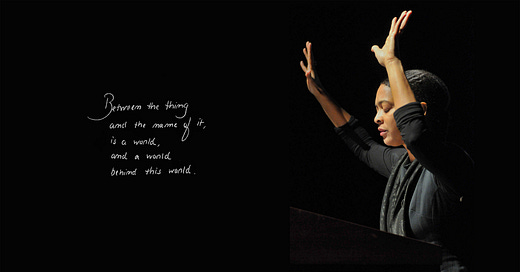

To my eyes that autumn day, nothing about the Danielle Legros Georges betrayed any illness. In fact, I thought she looked beautiful at the podium, and I wished that I could someday write poetry as impactful and eloquent as what she was giving us that day.

I write this now, five months plus a day after seeing her read in Newburyport. Today is the day after her 61st birthday, which she never got to see. Four days ago, Danielle Legros Georges passed away peacefully at home with her partner and brothers by her side.

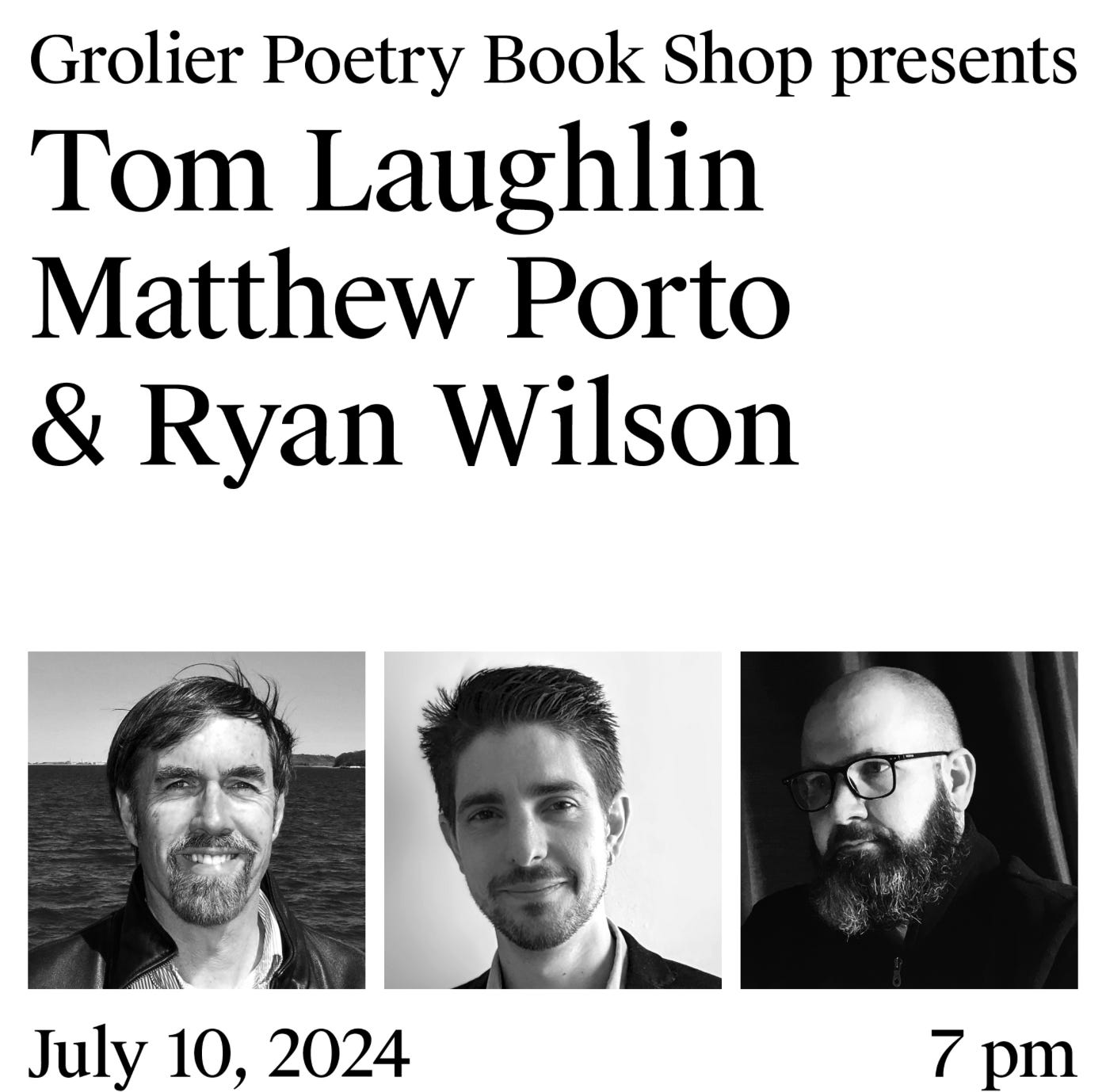

Proving how small the Boston poetry community is, I was also in the audience when Danielle’s partner, Tom Laughlin, read at the Grolier Bookstore in Cambridge on July 10, 2024.

It was a beautiful evening and the readings were, of course, amazing, but I was there to see my professor, Ryan Wilson. He’s written a number of books, but one that immediately comes to mind as I think about Danielle Legros Georges is How to Think Like a Poet.2

In the essay, Ryan Wilson focusses on xenia, which means guest-friendship or hospitality. As

recently pointed out, xenia falls under the category of social or community-based love. My friend mentions xenia in his latest post on Book 6 of the Iliad, when the mighty Diomedes encounters Glaucus,Diomedes learns their ancestors were bound by guest-friendship (xenia), a sacred bond of mutual respect and hospitality. Honoring this connection, they decide not to fight each other.

Xenia is love of the other, of the stranger, and the necessity of extending hospitality and love to someone you do not know. Ancient stories are full of foreigners who turn out to really be the hosts: Odysseus returning to Ithaka looking like a beggar, Zeus and Mercury appearing to Baucis and Philemon, and Christ coming into the world as a lowly child born in a manger — He who is actually the Son of God.

Why would we need to learn the virtue of this kind of love called xenia? Why is it important to the poet?

Art is how we convey to the next generation what we value. We must do so clearly and beautifully, so it is revisited, repeated and remembered. One basic belief is that every human should be treated with compassion and love, no matter how different they are from us. It means recognizing the foreigner and welcoming them, not assuming they mean to kill us. Maybe they do? However, so many of the old stories speak to the contrary. Xenia helped save Glaucus’s life from Diomedes who had killed so many up until that point in the Trojan War.

Xenia is a reflection of divine trust and piety, and through the exercise of guest-friendship cultural exchange is possible: art becomes enriched by other art, novel technologies are introduced or developed, and new social bonds and alliances are created.

By practicing xenia in our practical lives our civilization flourishes. However, Wilson notes:

We see all around us the dire consequences of such poor xenia. Our culture thinks of knowledge only as a means to power, a means to getting what we want: a grade, a job, a raise, a house, a car, fame, prestige, awards, and so on. Most of us treat the real world as a series of obstacles or impediments preventing the actualization of our personal idealized vision of what the world should be; most of us cannot even imagine what it would mean to treat the world with xenia. We dislike anything that is not exactly like us—though we shout “diversity” from the rooftops, really we’re scandalized by difference; we attempt to bend nature, and other people, to our will; we learn about the world only to manipulate it and to control it for our own benefit, or to inflate our egos; we learn about others only to “network” or to use them more efficiently for our own ends. We turn the stranger into a slave, and whip him within an inch of his life, and, in so doing, we create chaos in the world around us; faction and violence appear; blood stains the streets of our cities; mountaintops and rainforests topple; the water seethes with pollution; civilization declines. [Emphasis mine.]

In “A Stateless Poem” the stripping of citizenship of Dominicans of Haitian descent is a dehumanizing act, just as the stripping of Jesus before crucifixion was a public humiliation. The Golden Rule in Matthew 7:12 says that “In everything, do to others what you would have them do to you.” Yet we live in a world where we see this less and less.

It is easier to treat others well if we can see the beauty in the differences. Gerard Manley Hopkins sang the praises for a God who created the “dappled things” of this world:

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him. Glory to God who made things strange! They are beautiful.

Wilson points out that “Art must approach the stranger not with an eye toward enslaving it but with inquisitiveness and delight in it for what it is.”

However, Georges’s poem describes for us how our neighbor can easily be turned into a stranger. Through the exertion of political power, those who once had a state, and thus a homeland, can become without one. The speaker of the poem rightly asks: What are you? Who are you? In Roman Catholic teaching, caring for the homeless is a corporal work of mercy. A statewide action to strip a people of their home is then, by definition, merciless.

The profound gift of Georges as a poet is that her work speaks not just of the political. It is not propaganda. A lot of contemporary poetry falls into the trap of simply yelling out political grievances with messy enjambments. It never digs deeper; it only skims the surface of the au courant. However, Georges’s poetry isn’t afraid to go further, and her readers discover that below the surface of grievance is actual grief. And the deepest griefs speak to what men have loved and lost.

Love is the strongest social bond ever created. There is the reason why the ancient Greeks had so many names for it.

As a poet and teacher, Georges acted as the Greek god Hermes did, as a messenger between one world and another. Wilson reminds us that Hermes is the god thought to have first given mortals the gift of language. He was also a “guide of souls” (or psychopomp) because he was the god who helped usher the souls of the dead down into Hades. As a poet and translator Danielle Legros Georges was a psychopomp, helping her students and readers move from one world to another, allowing us to see a culture, a poetic language, we would not have been able access otherwise. And now that her soul has slipped these surly bonds of earth, her poetry remains as a way for us to understand the land of the foreigner. The dignity of the other. The strangeness of the good.

Just at the beginning of this month, Governor Healey signed an executive order creating Massachusetts’s first poet laureate position in the history of the state. When I heard this news, I swear, the first name that came to my mind was Danielle Legros Georges. To find out why, I invite you to read some of her poems via the links on her website. And here is where you can find out where to buy her books.

I regret not speaking to Danielle more when I saw her in September, but I am glad I was able to hear her voice and say that she is a part of my recent memory. I accept this as a small blessing.

Eternal rest grant unto Danielle, O Lord,

and let perpetual light shine upon her.

May her soul and the souls of all the faithful departed,

through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

Amen.

A funeral service is planned for the poet at 10 am on Saturday, February 22, at the Boston Basilica: Our Lady of Perpetual Help, 1545 Tremont Street in Boston.

Danielle Legros Georges

February 14, 1964–February 11, 2025

Author, Academic, and Translator

Poet Laureate of Boston (2015-2019)

I do not have the permissions to reprint this poem so I am providing a link. The poem appears in The Dear Remote Nearness of You (2016) and was republished in The New Daughters of Africa (2019). Many people do not have any problem reprinting poems for educational purposes, but I always like to try to get permissions beforehand. In this case, it is obviously very difficult.

How to Think Like a Poet is also available as a monograph from Wiseblood books ($6).

Thank you for sharing both about the life of a poet and a much needed message. Our society needs more xenia right now.

Zina, this is a beautiful tribute to Danielle and to the way of xenia. This rather simple call to action of loving the stranger is at the heart of so many religious doctrines and cultural ideologies. What a beautiful way to live a life. Thanks for this reminder.