Embracing Mercy

On the power of touch, do children have the right to hug their parents, David Roberts's posts on the justice system, and my experience with our church's prison ministry.

First, a mea culpa. Some of you may have noticed that I gave myself the week off. Such is this time of year with five children in three schools, winding down my own graduate studies for the semester, and all the end of the year events to navigate. However, to make up for my absence I will be posting a little more frequently than my usual. I hope you don’t mind, but if you do, please feel free to complain or propose something different via either of these buttons:

(BTW - I love this new Substack direct message system. You can use it for more than just complaints. You can even just say hi.)

As Leo Tolstoy wrote in Anna Karenina, “Spring is the time of plans and projects.”

One of my long postponed projects has been a basement clean out for which I recently enlisted a friend,

, to help me. As we were sorting through almost nine years worth of kid artwork I mentioned that the well-known family therapist Virginia Satir claimed,We need 4 hugs a day for survival. We need 8 hugs a day for maintenance. We need 12 hugs a day for growth.

I am fairly certain this is a hyperbole since there have been several days in my life where I did not get four hugs a day yet I still managed to wake up the next morning. Upon hearing Satir’s statement even my 8-year-old said, “That’s ridiculous!” However, since quitting my more stressful jobs and switching to being a paid caregiver of infants and young children my happiness has increased despite the bleak pay. I suspect that part of my contentment may have to do with the number of surprise hugs I regularly get from 3-year-olds.

Human touch is a very powerful thing. It can provide relief to someone who is suffering from pain or stress, decrease susceptibility to illness, improve heart health, and relieve fears for people who have low self-esteem. There are even studies done on how to hug and for how long.

One of the lessons many of us took from the pandemic was that there is such a thing as touch deprivation. A video screen will never take the place of seeing someone in the flesh and being able to embrace them. This is why a recent title in The New Yorker grabbed my attention:

“The Right to Hug” by Sarah Stillman exposes the fact that jails across America have replaced in-person jail visits with poor-quality video calls. GTL and Securus are the two companies that hold monopolies on video communications for the incarcerated. Instead of in-person visits where family members can hold hands and share meals, there are now kiosks where family members speak to each other over videos, sometimes hardly able to hear each other or are in danger of dropping out of the call. With no competition, there is little incentive to improve quality. Private equity companies make money off of these virtual visitations and other services, like charging five cents a minute to read books on tablets and selling digital “stamps” required to send messages to people on the outside.

Le’Essa Hill, one of the girls interviewed for the article said, “I actually remember how, the first time my dad got locked up, when I was about three years old, we were allowed to go see him in person at the jail,” she said. “That’s how I found out, ‘Oh, this is what my dad looks like, and this is what he smells like, and this is what he feels like.’ ” And then in-person visits ended and were replaced with an extremely expensive video service where sometimes Le’Essa and her sister could not even hear their father. There were times when their mother had to choose between keeping the heat or gas on in the house and paying the GTL bill.

Troy Lyle, one of the jailed fathers said, “You give us all these mental-health classes here, but then you take away our ability to see our kids!” he said. “Our families are a part of our mental health—we are worried about our babies!”

Families are one of the basic units of society. Once an individual gets out of incarceration, their ties to family will likely be a significant factor as to whether someone can successfully rejoin their community.

My friend,

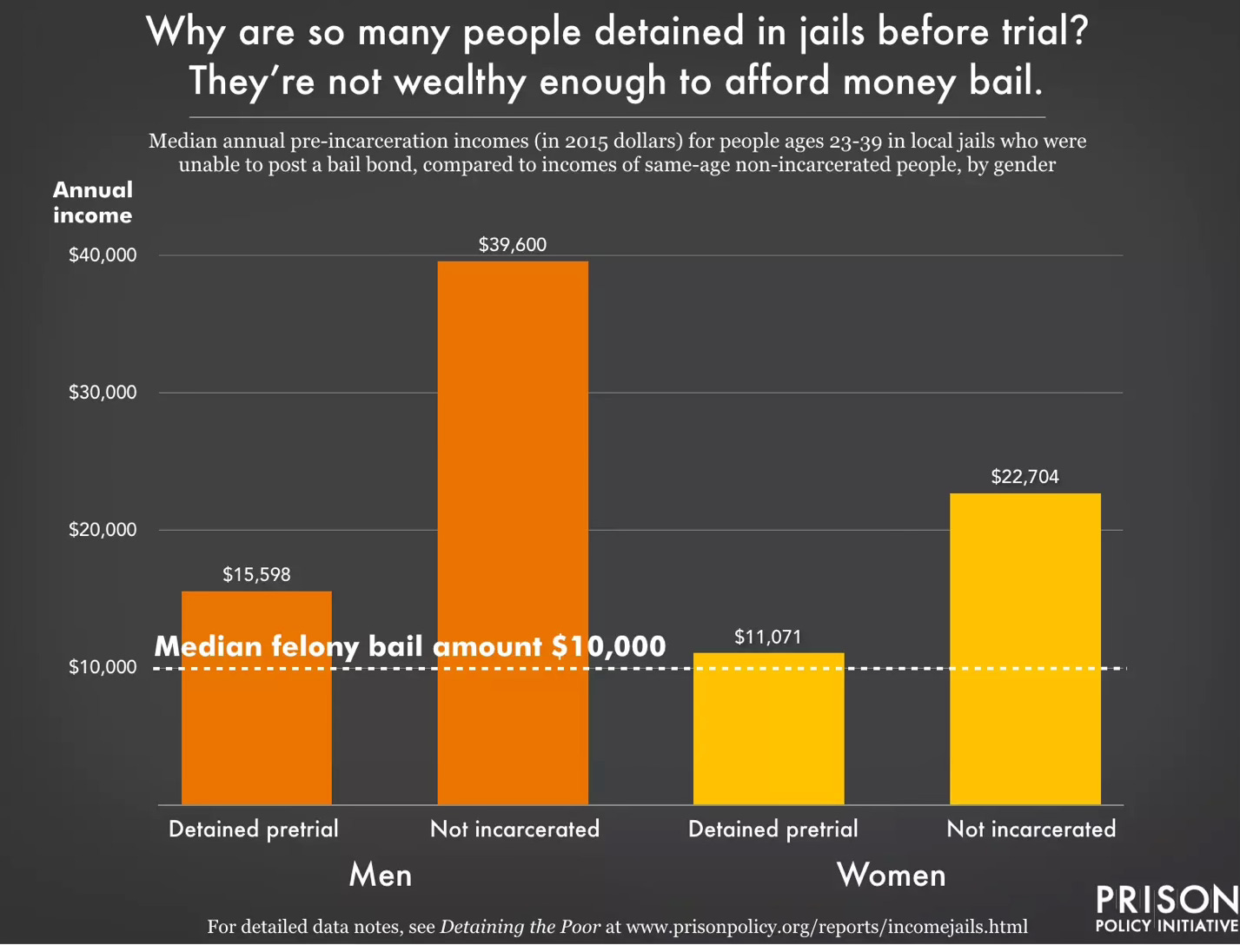

, recently wrote about his brother Samuel’s work as a public defender and the inequities in the US justice system. He says that although many of Samuel’s clients are guilty and should go to prison “far too many of my brother’s clients who are innocent end up serving long stretches of time in jail awaiting trial. Far too many prosecutions are capricious and unwarranted.”The majority of those who are jailed are not sentenced. Many inmates await trial in these facilities for years—this includes those who are innocent of the crimes for which they are accused.

I highly recommend that people read David Roberts’s two posts (here and here) which speak to socioeconomic disparities in our criminal justice system. I have another perspective from my own experience.

“I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

Matthew 25:36

When I lived in Baltimore in the early 2000s, I was involved in our Catholic church’s ministry that served incarcerated mothers. At the time I was challenging myself to look at the Corporal Works of Mercy, and I knew that one particular work—Visiting the Imprisoned—was one where people often had little sympathy. I saw my volunteering as a way to challenge my understanding.

The women’s ministry would go into the prison with a selection of books that the incarcerated mothers could read to their children. We would record them on CD and send the book and recording of the reading and personal message so that the children could still have a connection with their mothers. This was a very emotional project, and it showed me the intense the bond between a mother and a child—and how easy it is to irreparably damage.

It is worth noting that, although many people conflate jail and prison, these are two different institutions. Jail is typically for those awaiting trial or who have shorter sentences—typically less than a year. Prison is where those who have been convicted of a serious crime usually serve their time. The church group I worked with went to the prison, but I could not help but try to understand how the whole criminal justice system worked, including the jails.

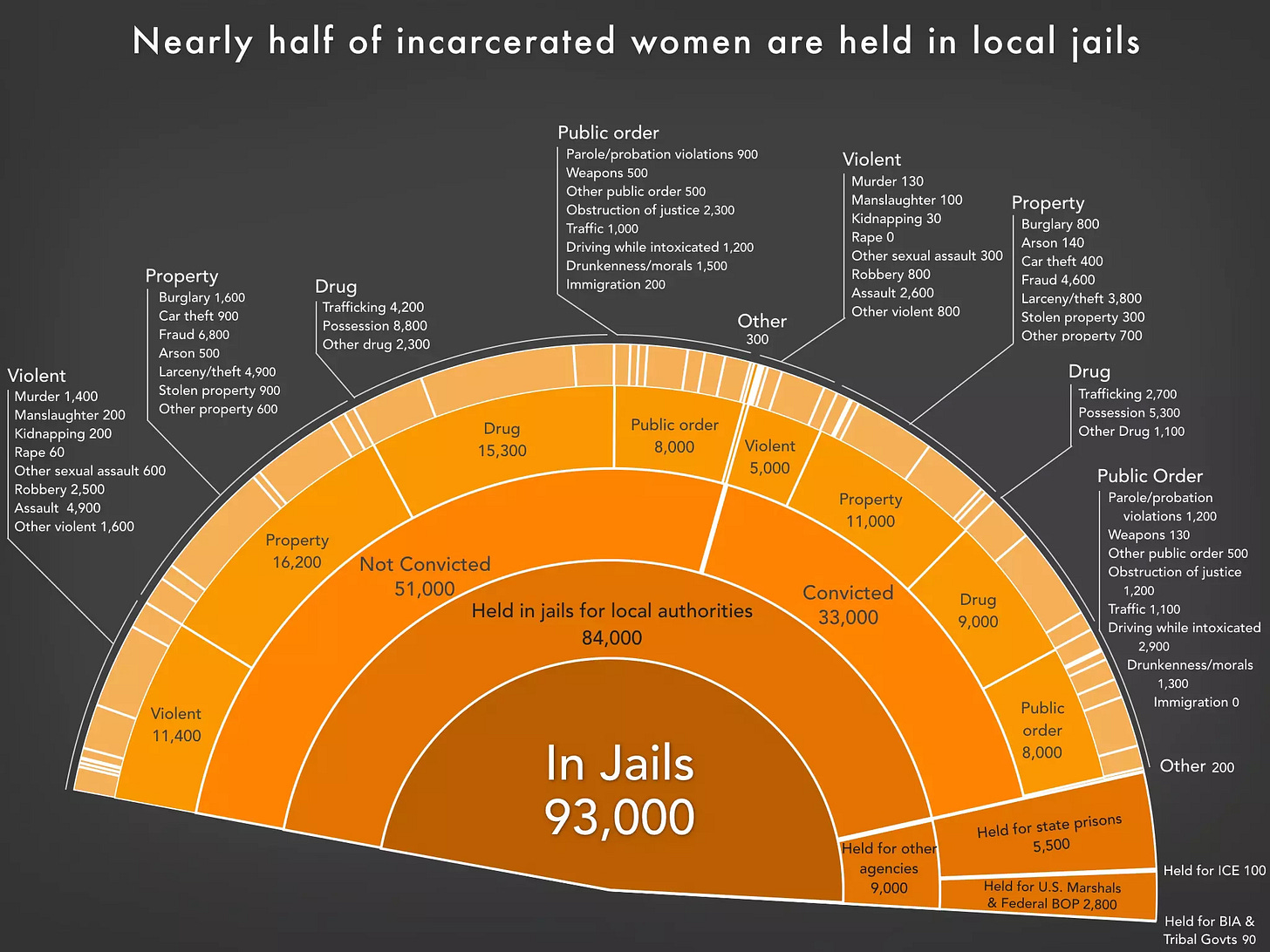

A lot of criminal data is male-centric, but the Prison Policy Initiative offers a more thorough picture of the very different situation for women in jails. Since women are more likely to be serving time for non-violent crimes like property or drug offenses they are also more likely to remain in jail instead of getting sent to prison because their sentences are typically less than a year. Women have a higher mortality rate than men in jails, which includes death by suicide.

About communication, Prison Policy Initiative notes:

Jails also make it harder to stay in touch with family than prisons do. Jail phone calls are often at least three times as expensive as calls from prison, and other forms of communication are more restricted — some jails don’t even allow real letters, limiting mail to postcards. Increasingly, both prisons and jails are doing away with real mail altogether and contracting with private companies that scan and then destroy postal mail, delivering shoddy scanned copies to the recipients. These barriers to authentic communication are especially troubling given that 80% of women in jails are mothers, and most of them are primary caretakers of their children. Thus children are particularly susceptible to the domino effect of burdens placed on incarcerated women.

Note: Inmates in prison are actually more likely to get in-person visits than those who are in the jail.

Prison Policy Initiative also makes another distinction between men and women who are incarcerated [emphasis mine]:

While drug and property offenses make up more than half of the offenses for which women are incarcerated, the pie chart reveals that all offenses — including the violent offenses that account for over a quarter of all incarcerated women — must be considered in the effort to reduce the number of incarcerated women in this country. This fact underscores the need for reform discussions to focus not just on the easier choices but on the policy changes that will have the most impact. Particularly in light of the fact that many survivors of domestic and sexual abuse have been incarcerated for violent crimes that occurred in response to gendered violence and abuse, exclusions from reforms based on entire offense categories make even less sense.

When looking at all the statistics it becomes very apparent how we need to view the different sexes, how to effectively address those who commit egregious crimes and protect society while also treating the accused with human dignity and with an understanding of the effect incarceration has on innocent family members and children who are active members of our communities.

I am reminded of Portia in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice where she speaks of the quality of mercy [emphasis mine]:

The quality of mercy is not strain'd.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

'Tis mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes

The thronèd monarch better than his crown.

His scepter shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptered sway.

It is enthronèd in the hearts of kings;

It is an attribute to God Himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God's

When mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew,

Though justice be thy plea, consider this:

That in the course of justice none of us

Should see salvation. We do pray for mercy,

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy. We all want justice.

We all want a just world where evil deeds are punished.

We all want goodness to prevail.

However, we are all humans with faults. We are all sinners—every single one of us. I have lived long enough on this earth to personally see people of privilege come away from doing stupid things without a black mark on them. And I have seen people who are not born to that privilege do the same things and fall hard because of lack of money, family and influence.

It is worth noting again that there are many people in jail who have not been convicted, and many of them remain there because their families cannot afford to post bail.

I don’t know how to solve these problems, but I know the first step is to be aware that these inequities exist. I am grateful that there is a list of Corporal Works of Mercy, and that I knew enough to use it as a guide to help me decide where the volunteer because it opened my eyes to a world I am not sure I would have seen otherwise: the lives of imprisoned mothers.

I pray for mercy, as Portia says. I pray that we as a society learn to show more mercy, and for that mercy to abundantly season how we practice justice.

Zina

The Portia speech was very moving to read after your post

I will share with my brother Sam who will be interested in your comments about the restrictions on family contact with prisoners

I can’t see a purpose in it other than cruelty

Do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with our God. Easy, right? Hahahaha.