As Mnemosyne Would Have Wanted

Celebrating my birthday early at Frost Farm, the New Verse Review, an unpublished ekphrastic poem, and (yet another) an argument for memorization.

Hello, dear readers. Apologies for the highly unusual absence! After more than a two-week drought of posts I wanted to let you know that you will likely see some posts in quick succession—of various different types but mostly concerning the Frost Farm Poetry Conference which I attended this past weekend. This has quickly become my favorite annual literary event. With workshops, good food and drink, and intellectual fellowship for two and a half days up on the hallowed ground of Robert Frost’s farm, it’s hard for someone like me not to feel nourished. Attendance is capped at just 50 participants so writers have the opportunity get into deep conversations with some of the best in the business, like Rhina Espaillat, A.M. Juster, Ned Balbo, Jane Satterfield, and others.

On the first night I got to meet was

, the editor of the new literary journal . As mentions in one of his latest posts at , NVR may be able to fill the void left by the likely closing of Literary Matters. The inaugural edition features Jared Carter, Maryann Corbett, Len Krisak, Amit Majmudar, Benjamin Myers, Dan Rattelle, J.C. Scharl, Matthew Buckley Smith, Marly Youmans, and many great poets. I also recognized friends among the contributors, like Elijah Perseus Blumov, the host of the Versecraft Podcast, and , who co-authors the Substack . I found my MFA program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston well represented with poems by my professor James Matthew Wilson and fellow UST graduate students, Christopher Honey and Mary Grace Mangano.Two of my UST classmates, Daniel Cooper and Sarah (Spivey) Ashbach, were also at the Frost Farm. Sarah was this year’s winner of the Frost Farm Prize in Poetry. It was so wonderful to hear her read “The Dispossession” on the first night because I remember first encountering it in our workshop at UST.

During the participant readings, Daniel shared his poems “Moby Dick” and “Petrarch On (Not) Reading Dante,” both of which can be found in Light Poetry Magazine. And my friend James McBride read his poem, “The Prefect of Judea,” which won the this year’s Catholic Literary Arts Sacred Poetry contest.

And, of course, I had my turn at the microphone. I am especially thankful to David, James and Steve for sending me pictures.

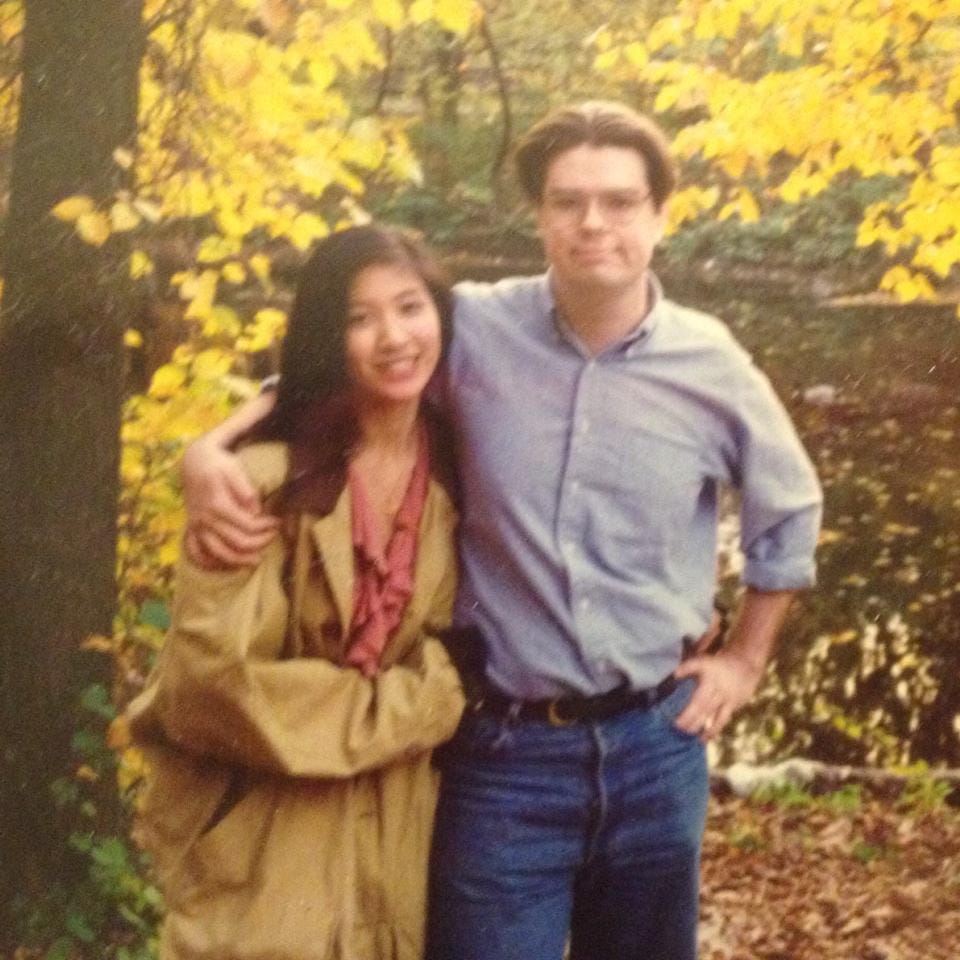

Some of my readers have mentioned how much of my poetry I don’t share,1 so I thought I would offer you the first poem I read and the picture on which it is based.2

Photo by the Potomac, October, 1994

Could we have been so young? Sometimes I stare

At us beneath the leaves—no, not just friends.

The light is glinting off the river, there

Behind us, as we look into the lens

To smile our careless smiles. How unaware

We were of the jobs we’d quit, the moves we’d make,

And all the kids we’d had—without a plan.

And there were many times I thought we’d break—

But hell, my love, I’d do it all again

With just these rings—no guests, no gifts, no cake.

In that old photo I can see your face,

Too young to think of any wedding bands,

But look at how two lives can interlace

Like fingers with our little children’s hands

Or like these quiet nights when we embrace.The poem is a still a work in progress, and even if I manage to “finish” it I won’t be sending it out anywhere. It’s not really a public poem. Probably not my best poem either, but of all the things I have written, it’s the one closest to my actual speaking voice. It is the easiest one for me to remember—and thus recite. I also knew my second poem fairly well, but I had so many last minute changes I needed to look at a marked up copy. However, if given more time, I probably would have been able to recite that one too.

One of the joys of formal verse is that there are so many “handles” onto which Memory can grasp. Rhyme and meter make reading aloud and recitation so much fun to perform—even if just for one’s self. I’ve heard that some poets cringe when they read their own poetry out loud. I can’t even imagine that. If you don’t enjoy the sound of your own poetry why on earth would you subject it to others?

The highest goals I have for my poems are that they be musical and memorable.

As Dana Gioia proposes in his essay, Poetry as Enchantment,

The best way to engage the imagination of students is to augment critical analysis with experiential, performative, and creative forms of knowledge. Memorization and recitation should be restored as foundational techniques. Bringing students the pleasure and exhilaration of poetry is necessary before the analysis of it has much relevance to them. There should also be creative forms of engagement such as writing imitations, responses, and parodies, or setting poems to music. Students need to have more experience listening to poems aloud, even though that takes up finite classroom time. Reading poetry silently on the page (or aloud in little snatches) as part of textual explication is an incomplete introduction to the art. It is drab and bloodless like viewing the masterpieces of Cezanne and Van Gogh in black and white reproductions. One sees some wonderful things but also misses something essential. Like song or dance, poetry needs to be experienced in performance before it can be fully understood.

The idea that “poetry needs to be experienced in performance before it can be fully understood” is something that appeals to me, a kinesthetic learner. I was not as good of a student as most people think. I fought for every decimal point on my GPA. Now that I am older I know now that I need to read everything out loud or listen to things while I am moving. Language for me is embodied and physical, not just some coded set of symbols on a page. I’ve developed a highly personal process around writing poetry that requires vocalization—from first draft to last revision—which has made memorization somewhat involuntary.

It isn’t that dissimilar from learning new prayers. The more we pray the less we have to think about praying. The words become muscle memory and the text transcends sound and moves into meaning and emotion.

However, this type of poiesis is a painstaking slow process, and it means that I don’t have as many poems as many of my peers. It reminds me of visual artists who work with media that is applied in layers that need to dry or cure. There is no rushing to the next step. It is an art that requires patience. Not everyone works like this, and perhaps this isn’t how I should work either, but in this novitiate season of poetry I’ve experienced a great (there is really no other word for it) joy when my main instruments are Memory and Body.

Just as the Muses are the daughters of Mnemosyne, our own artistic endeavors are the children of our memories. In his essay, Gioia points out Robert Frost’s definition of poetry as “a way of remembering what it would impoverish us to forget.”

Frost’s pithy definition is usefully ponderable. He calls poetry “a way of remembering,” which is to say a mnemonic technology to preserve human experience. He claims the loss of what it preserves “would impoverish us,” which is to say that poetry enriches human consciousness or, at the very least, protects things of common value from depredation. Finally, he asserts that poetry maintains these virtues against the human danger “to forget.” Here Frost acknowledges that the art opposes the natural forces of time, mortality, and oblivion, which humanity must face to discover and preserve its meaning. As Frost said elsewhere, one of the essential tasks of poetry is to give us “a clarification of life . . . a momentary stay against confusion.”

It is interesting to read these words now—after having studied poetry on Frost’s actual farm with some of the finest formalist poets writing in the English (and, in the case of Rhina Espaillat, Spanish) language. It seems like too lofty a goal to write something that will outlive us, and yet there is so much Beauty in the world that we ought to try.

Our culture uses Forgetting—distraction as entertainment—as a way to numb us into mere survival. But Remembering is the tool we must use to answer the essential question: Why live?

I believe that Poetry, the daughter of Memory, is capable of answering this question.

The photo may look familiar because I used it in this older post about Jean Pierre de Caussade’s Abandonment to Divine Providence.

I'm new to your writing, but if that 'probably wasn't [your] best' poem I'm in for a treat! Thank you for sharing something so personal

I enjoyed reading your thoughts on the sound and performance of poetry. Almost simultaneously I read Mary McCray’s “Should Poetry Be Heard or Read” over at Big Bang Poetry. Talk about serendipity.

I go back and forth on this. Right now I think I’m with McCray because my mind tends to wander or skip around when I hear an unfamiliar poem read aloud. But I also think that reading aloud must be part of the poem’s composition process, if only to catch clumsy language. Perhaps having someone else read a poem aloud would be even better: if they stumble over a word or passage, then that might be a place that needs work.

I honestly wonder how many poets read their work aloud at each stage of development. I was kind of shocked years ago to come across this quote by Sylvia Plath from an interview: “My first book, The Colossus, I can’t read any of the poems aloud now. I didn’t write them to be read aloud. In fact, they quite privately bore me.” Are we separated now from mid-20th century poets in this regard, or are things still pretty much like that?

https://www.bigbangpoetry.com/2024/08/what-is-poetry-heard-or-read/