Tenebrae, Bigotry, and Flannery

Reading the part of Pontius Pilate for Good Friday Mass and “Everything That Rises Must Converge” for The Catherine Project

Dear Readers, I know that it is highly unusual for me to post so soon after the last essay. I am extremely sensitive about overwhelming your inboxes because I’m often drowning in mine, but there is a certain timeliness to this one.

First, let me explain something. I volunteer as a lector at my parish, and this year I’ve been scheduled for Palm Sunday, Good Friday, and Easter Sunday. Being a lector is a wonderful gift as a poet. It is like doing a reading but with a much better author. Like Palm Sunday, yesterday’s Good Friday service was a dramatic reading with three speakers, and I had the parts of Peter the Apostle and Pontius Pilate.

There is an exchange between Pilate and Jesus that begins with the Roman leader asking, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus replies, “You say I am a king. For this I was born and for this I came into the World, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”

And Pilate asks,

“What is truth?”

Throughout the Gospel, Jesus says the truth of who he is over and over. He does not present himself otherwise, yet Pilate, a man of no religious faith, is blinded to the reality of who stands before him. Jesus is the truth, but Pilate is a man who does not belong to it. He is unable to listen with any understanding to what Jesus is saying. Despite not believing in Jesus as the Messiah, Pilate still has a sense of justice to know that he cannot convict Jesus of wrongdoing.

Pilate, not wanting to send an innocent man to his death, tries to appease the Crowd by having Jesus scourged and mocked with a crown of thorns and purple cloak. When this torture is not enough for the Crowd, Pilate concedes to the Crowd’s call for crucifixion.

This reminds me of a poem written by J.E. McBride1 which won the Catholic Literary Arts Sacred Art competition last year. “The Prefect of Judea” (an ekphrastic poem inspired by Munkácsy’s Christ Before Pilate) ends in chilling administrative understatement:

Today it means the cunning compromise, tomorrow the razing fist. Fools in fora and the halls of senate speak of truth Like boys in bloom boast with tales of women’s bodies But it is here along the edges of the map where unsung men Weave its boundaries from the void and seal them with the stamp of death.

And so, a day like any other. He lifts his hand, he speaks, he writes. Hesitates for a single moment, does not erase what he has written.

Nearing the end of Pilate’s role in the Gospel, I spoke the words of the weary leader,

“What I have written, I have written.”

As a lector standing at the altar, it is a shocking to be on the receiving end of a congregation shouting,

“Crucify him! Crucify him!”

In a perversion of justice, the Crowd demands that Barabbas, a rioter and murderer, be released instead of the innocent Jesus. At the end of the Gospel reading, the Son of God dies and is laid in a tomb. We had a veneration of the cross and a solemn procession out of the church.

In my head, these readings were in conversation with the assignment for this Monday’s Catherine Project class: Flannery O’Connor’s “Everything That Rises Must Converge” — a short story laden with Christian imagery, especially pertaining to judgement, persecution, sacrifice — and ultimately knowing who you really are through the consequences of your own actions. 2

I have been an active member of the Catherine Project community for a several years now. This summer I will be co-leading a group that will be discussing Geoffrey Hill’s book of poems, “Tenebrae”3 , named after the religious service celebrated during the three days before Easter — the period of time during which I am writing this post. Talk about convergence.

I’ve read “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” several times and O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood, but it was not until Good Friday that I had even looked at “Everything That Rises Must Converge” which is one of her most famous stories. I am not sure I would have taken as many notes had I not already been steeped in the Passiontide.

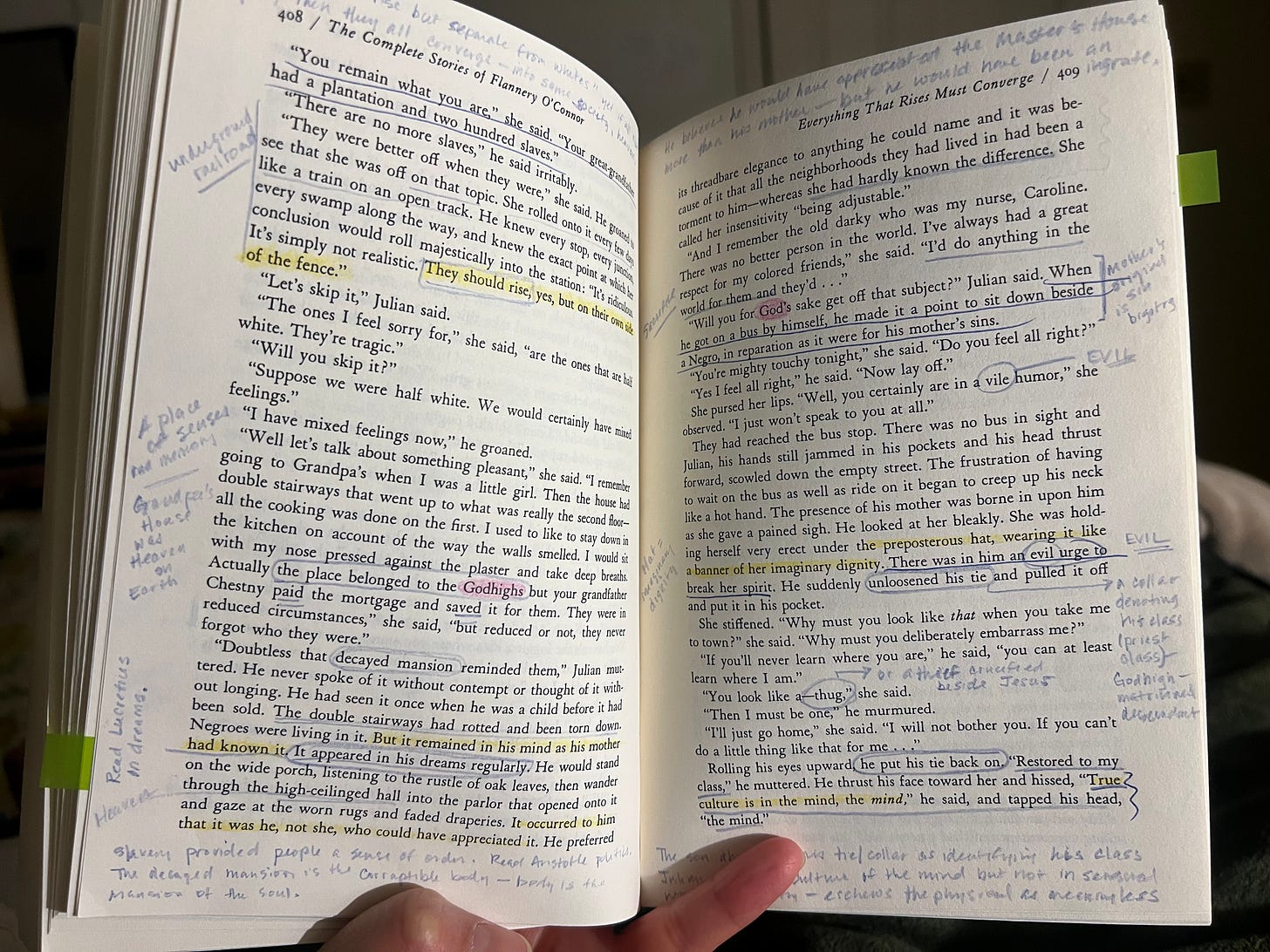

“Everything That Rises Must Converge” is a mother-martyr cliché turned on its head. It is also an interesting take on the idea of bigotry, which is a stronger word for prejudice, which comes from the Latin praeiūdicium which comes from prae (before) and iūdicium (judgment). The irony of O’Connor’s story is although the mother is against desegregation, the real bigot is her son Julian who hates small-minded, anti-intellectuals like his mother. His prejudice crosses the line into bigotry because his biases are not just fearful — they are hateful. He takes perverse pleasure in making his mother suffer because he believes she needs to be “taught a lesson” for being a racist. Julian does this despite the fact that his mother loves him and is a widow who made significant sacrifices to send her son to college. In many instances, her actions are gracious and kind even if her words betray a fear of integration and how it may change the world as she knows it, which is why she asks her son to accompany her on the evening bus.

The only real loving mother-son moment is the brief one between Julian’s mother and Carver, the 4-year-old black boy on the bus. The white woman and the black child clearly enjoy sitting next to each other, even playing peekaboo. Every time Carver’s mother pulls her son away, he tries to go back to Julian’s mother. Upon disembarking from the bus, Julian’s mother tries to offer Carver a shiny copper penny. (A gift freely given, like God’s Grace, a sign of His unconditional love.) Carver’s mother is offended by the gift, and she assaults the white woman, knocking her to the ground. Instead of helping her up Julian yells at her.

“I told you not to do that,” Julian said angrily. “I told you not to do that!”

He stood over her for a minute, gritting his teeth. Her legs were stretched out in front of her and her hat was on her lap. He squatted down and looked her in the face. It was totally expressionless. “You got exactly what you deserved,” he said. “Now get up.”

Hate has a way of feeling like righteousness, doesn’t it? The bond between mother and child is one of the strongest relationships, and yet hate can destroy even that. It reminds me of this recent article in The New Yorker entitled, “Why So Many People Are Going ‘No Contact’ with Their Parents: A growing movement wants to destigmatize severing ties. Is it a much-needed corrective, or a worrisome change in family relations?” I am not judging anyone’s particular family situation because I know there are many abusive family relationships. However, I know anecdotally there are incidences of prolonged political disagreements that are a growing reason why family members do not talk to each other, and I wonder if a lack of empathy and sympathy towards each other is causing a greater societal fracturing. Are some of the most violent incidences in the greater world created not by decisions made on a large scale but by the disintegration of close family relationships?

The realm of politics and policy is not my domain, but the issue of prejudice and racism isn’t political for me. It is personal. I am a first generation Filipina-American who grew up in the 70s through the 90s in a very racist Boston. Rocks had been thrown at our house when I was little. I’ve had all types of [redacted] said to me growing up, and I don’t feel like rehashing all of that in this essay. After living in DC, Baltimore, and Silicon Valley, I came back to my hometown in 2005 to a place that is more accepting of my skin color — but a lot more intolerant of socially conservative values. This isn’t to say that I am on one side or another; I am a true moderate, one of the most frustrating data points in the world. However, since I was a young child I learned to survive by staying quiet — observing, not reacting, and trying to be aware of my place in a community. I’ve learned that everyone is biased, and the worst offenders are the one’s who deny it and justify their positions with righteous anger and the groupthink. Remember: it was not one person who caused Jesus’s execution. It was many. The highly educated men of the Sanhedrin. The crowd yelling in a unified voice for blood.

“Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

The tragedy of the Passion was that Jesus was innocent, but he was tortured, taunted, and killed anyway. We are told that He died for our sins, and as a Christian I believe this. However, I know that Christian righteousness has been used to persecute and subjugate people. Ironically, this part of the Gospel has been used to justify centuries of anti-semitism. Other parts of the Bible have been used to justify slavery or misogyny. Jesus’s stories of mercy, forgiveness and loving one’s neighbor are forgotten when they are inconvenient.

I don’t tell anyone what to do or think, but I can tell you how one scene between Julian and his mother gave me pause — made me reconsider who I was and whether I was a good person.

Before getting on the bus, Julian has the “evil urge to break her spirit” and removes his tie. She accuses him of trying to embarrass her, and when she says he looks like a thug4 he relents.

Rolling his eyes upward, he put his tie back on. “Restored to my class,” he muttered. He thrust his face toward her and hissed, “True culture is in the mind, the mind,” he said, and he tapped his head “the mind.”

“It’s in the heart,” she said, “and in how you do things and how you do things is because of who you are.”

“Nobody in the damn bus cares who you are.”

“I care who I am,” she said icily.

We often overestimate how good we are, and Julian does this repeatedly throughout the 21-page story. He is constantly imagining how his open-minded liberal views on race can be used to torment his bigoted, small-minded mother. He believes she doesn’t have any right to any happiness because of her worldview, despite her actions speaking to the fact that she really loves people, despite their skin color — whether that be Caroline her black caregiver when she was a child or Carver the little boy on the bus. Someone can be prejudiced and yet innocent of any crime. Someone can have a wrong opinion, but that opinion doesn’t not justify physical, mental or emotional abuse. Just because someone doesn’t believe in [fill in the blank] rights does not mean that they should die. Just because someone has a certain bumper sticker supporting a candidate you don’t like doesn’t mean you get to cheer when they get in a car wreck. Schadenfreude is an evil emotion, and I have heard people gleefully relate when something terrible happens to a stranger than they disagree with. When you wish ill on someone because you disagree with them, you are bad as Julian.

I’ll end this by describing my own bias. I don’t like the works of Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Victor Hugo, Willam Carlos Williams, Czesław Miłosz and more. It isn’t that I think their art is bad or offensive. In fact, I think they have contributed significantly to their respective arts. However, I despise these artists because I don’t like how they thought of or treated women. I’ve read things about these men that make me physically sick. In my mind there is a Dantesque circle of the Inferno where I’ve dumped a bunch of people. I fight my own impulses to join cancelation movements of certain male artists. As a Catholic, I should pray for their souls. I ought to believe that people can repent and change. But it is hard. I want to yell,

“Crucify him! Crucify him!”

But are we not all sinners? The sins of the past don’t have to define who we are going forward. We should work toward the rehabilitation of souls. Maya Angelou said, “When we know better, we do better.” In an instant, Julian changes when it is clear that his mother is dying. Some readers would argue that the change comes too late, but for someone like me the fact that the change happens at all is the entire point. Tragedy is a matter of timing when the story ends. Flannery O’Connor is like Pilate:

“What I have written, I have written.”

She wants us, as the Crowd, to judge Julian as the man who finally realizes he loves his mother—as he calls out in vain for help in the darkness.

Like O’Connor, Jesus was a storyteller, and Julian is the obvious Prodigal Son. His mother is from the matrilineal line of Godhighs, and the tie Julian attempts to remove is like the collar of a priest class. Her grandfather was a slaveowner. This is likely offensive to modern American sensitivities, but some of the most significant parables in the Bible are about Masters and slaves. It is a metaphor Jesus uses to teach truths about our relationship with God the Father. The irony here is that Julian’s idea of Heaven seems to be the slave master’s house of his mother’s childhood.

You have to know who you are, and that’s hard to do when you are constantly in your head justifying your own opinions or when you are in an irrational crowd calling out for someone’s blood as reparation for their sins. (And there is never enough blood. Hatred has a hunger that is never satisfied.) Sometimes the best way to know who you are is to pay attention to how you treat other people. Are they hurt by what you say or what you do? To paraphrase Julian’s mother,

True culture is in the heart and in how you do things —

and how you do things is because of who you are.”

Julian is an example of C.S. Lewis’s “men without chests” meaning that even if a man is well-educated he needs to have the chest, the heart his mother speaks of, to moderate between his intellect and his appetites. A lack of chest leads to a decay of morality in a man and a lack of virtue within society.

“A persevering devotion to truth, a nice sense of intellectual honour, cannot be long maintained without the aid of a sentiment... It is not excess of thought but defect of fertile and generous emotion that marks them out.” — Abolition of Man

A culture of love will never be free of bias, prejudice, or bigotry. But we can be loving people despite that. We can give people as much grace as we can because grace is what we always receive from God who always loves us and forgives us if we come to him. Holy Week reminds us about the pain of persecution and mockery.

If we say we are good people, we must act like good people who are merciful, compassionate, and forgiving. Maybe you don’t believe in being merciful, compassionate, and forgiving. If not, don’t worry. I won’t judge you. But I might pray for you — just as I pray for myself because I may be more broken than you.

Tragedy is a matter when the story ends, but Jesus’s story does not end today on Holy Saturday. It ends in the rejoicing of Easter tomorrow.

Until then…

I’d love to hear from you!

Have you read “Everything That Rises Must Converge”?

How much Flannery O’Connor have you read?

Do you celebrate Holy Week or any other religious holiday? How does it make you reflect on who you are?

For Catherine Project classmates:

My Random Notes About “Everything That Rises Must Converge”

Carver reminds me of Mt 19: 14 — Jesus said, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of heaven belongs to such as these.”

The name Julian suggests Caesar — is regal and somewhat pretentious. But also a worldly leader rather than the heavenly king.

Carver’s name may be inspired by George Washington Carver but also the act of carving wood. Carpentry, Christ’s profession, is also a form of woodworking.

Julian’s and Carver’s mothers are never named. It is a sign of their insignificance (we make special and particular through naming) or their universality (anyone’s mother). However, having the same hats and being heavyset may be the only similarities between them. Carver’s mother has more alike with Julian in terms of temperament.

Martyrdom syndrome is most commonly associated with the suffering mother, but Julian is the one who seems to have the “martyr complex” — as the reference to St. Sebastian makes clear.

“Julian raised his eyes to heaven” like many artistic depictions of St. Sebastian.

Words or phrases are repeated (mostly within a page of each other) like pleasure, gracious/graciousness, God/Godhigh, “had won,” “at least I/you won’t meet myself/yourself coming and going,” sacrifice, blood pressure, “teach her a lesson,” smile, and fun/funny.

On Easter women were known to have worn hats into church while men’s hats were taken off. It is a sign of respect to God.

The mothers’ hats are purple and green, evoking the purple robes of mockery that Jesus wore when he was beaten, spat at, and crowned with thorns. This is another crown of mockery as Julian thinks it is a hideous hat, and he lies about liking it.

Julian lies to himself about not being dominated by his mother and her small-mind. And “he was free of prejudice and unafraid to face facts.” He does not accept the healthy ordering of the universe where you honor your parents, even if you disagree with them. (There is always something to disagree with regarding one’s parents.)

The mother found joy in suffering, but this is horrifying to Julian. “He could not forgive her that she had enjoyed the struggle and that she thought she had won.” Modern Americans are particularly hostile to the idea of “needless suffering” and “unnecessary pain” — we have grown accustomed to a level of comfort and do not understand a redemptive “offering up” one’s pain for another as a type of sacrifice that also brings us closer to God.

Julian is a misanthrope who loved to be in his mind. “It was the only place where he felt free of the general idiocy of his fellows. His mother had never entered it but from it he could see her with absolute clarity.” (Also a lie.) He also imagines moving to a place where his nearest neighbors are three miles away.

Julian’s grandfather was a landowner and grandmother was a Godhigh (the maternal surname, a family of distinction).

The mother wears a hat and gloves to the Y (Young Mens Christian Association) for a women’s weight loss class — as if she is going to church. She is going to the Young (Wo)Mens Christian Association. It is a place that has free services. Like a church it offers well-being and community.

The trip to the Y is like a path to the mother’s healing and salvation. The doctor is like God who is the healer of the soul. Hospitals are often a stand in for heaven but here it is the Y. The class is prescribed to the mother; however it turns out a journey to her “cruxifixction” — not unlike Jesus being allowed to be the Paschal sacrifice.

Julian sits next to a well dressed black man thinking he’s a doctor or lawyer, but he feels betrayed when he finds out it is an undertaker. He is prejudiced by education class, not by race. Undertakers are like Charon, and this bus trip is like a ferry to the underworld.

Despite being racist, the mother is actually quite innocent and depicted in angelic terms. “Two wings of gray hair protruded on either side of her florid face, but her eyes, sky-blue, were as innocent and untouched by experience as they must have been when she was ten.”

Like Mary the mother of Jesus, this woman is a widow and raised her son into adulthood on her own.

On graciousness, the mother says, “Most of [the women in the reducing class] are not our kind of people,” she said, “but I can be gracious to anybody. I know who I am.”

The grandfather’s mansion appeared in Julian’s dreams regularly. It was like an Eden that he was barred from entering due to the original sins of Eve. In the American south the original sin is slave ownership.

Julian suffers a sense of entitlement when thinking of his mother’s childhood home. “It occurred to him that it was he, not she, who could have appreciated it.” It bothers him that she didn’t seem bothered by the permanent exile — even thought it was sustained by the evil of slavery. Irony!

Describing Julian’s humor, vile is just the word evil, rearranged.

Not only are the mother’s wearing the same hat, but the little boy is wearing a Tyrolean hat (very German and also suggesting racial prejudice).

Julian sees himself as a better class of person, not unlike the Sanhedrin and how they thought of themselves compared to Jesus. Julian is condescending in a hateful way. Jesus was born in a manger and lived a humble life, but he always knew he was the Son of God and his was the Kingdom of Heaven.

Julian disobeys basic commandments about honoring his mother, taking the Lord’s name in vain, coveting his mother’s childhood home, and lying to his mother and to himself.

“His soul expanded momentarily” when imagining himself in the restored Master’s House.

He fantasizes about being with a woman who is (suspiciously) black, beautiful, intelligent, dignified, and “even good” — and she suffered and hadn’t thought it fun like his mother says she does.

Julian is like Longinus the Centurion who was the deliverer of the last of the “Five Holy Wounds of Christ” — the piercing of Christ’s side from which blood and water poured out. (The mother suffered from high blood pressure — in a sense this relieved it.) He is thought to have converted it Christianity afterwards.

J.E. McBride is a friend, and he has a Substack as well.

It is great pleasure to be taking this class with my friend

of the excellent Substack, . Check it out if you can. We recently co-edited a small anthology:Sadly summer registration for the Catherine Project is closed — I meant to give everyone a heads up. Sorry!

When she says this it reminds me of the thieves who were crucified beside Jesus. Is Julian the good thief or the bad thief? Since he converts in the end, I believe he is meant to be the good thief.

I read some Flannery in college; but I didn't enjoy her much. She's the kind of writer I've always felt: she's good, but she's a lot of work. I can read her for a class and appreciate her craft and her deep insights through the lens of discussion and piggybacking off of other people's better reading skills; but she's not a writer I will read for pleasure and when I read her on my own, I usually feel stuck. Maybe I need to reassess my reactions now in middle age. Maybe I'm a better reader now than I was then and maybe I will appreciate her more now. But probably still not an author I will read for pleasure. More for illumination and appreciation.

I thought I had read this story before, but reading your description, now I wonder if I really did. I think I will sit down and read it today. It feels really relevant and important. I will enjoy reading it through your eyes and with your insights, especially in the context of Jesus's passion and his parables.

These reflections are encouraging, enlightening, and very helpful for Easter Sunday. At the Easter Vigil last night, I met one of the converts and had a good conversation, and I have just talked with by brother on the phone. Affection, mutual advice, good memories in spite of various difficulties over the years, and, of course, memories of O'Connor's works, "Everything That Rises" perhaps most of all, for Easter, and because i grew up in New York City, riding on bus and subway and meeting all sorts, occasional racists included. May our problems, political and others, not keep us from the convergence. Peace, Phil O'Mara