"Tell me about a complicated man..."

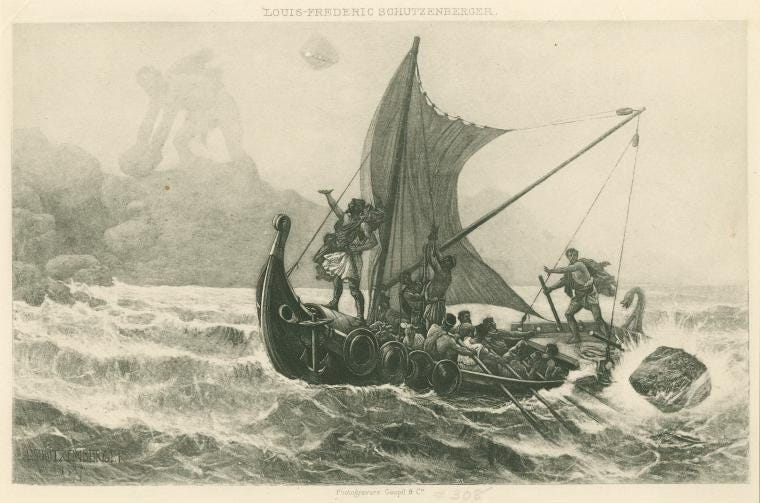

Reading about the crises of modern manhood while studying The Odyssey

Chances are if you are a man writing on Substack, you may have been distracting me for months.

Months!

I have been trying to write an essay about the first four books of The Odyssey. The Telemachy depicts a young man who has no male role model in his life. His home is full of suitors who are harassing his mother and steadily consuming everything they own.

The Telemachy is what it looks like when a young man has never had formation in what it means to be a man. This is traditionally the job of the father, but Odysseus never returned home from the Trojan War. However, with the help of Athena, Telemachus sets off to find him. And meanwhile, Odysseus is trying to make his way back to Ithaca.

But I am distracted…

by stories of men struggling. I see young people who are just starting their lives, trying to find love, a vocation, and a way to provide for themselves. I see middle-aged men going through job losses, separations, and struggles with mental health. I see men getting older and coming to terms with their aging bodies—trying to feel the dignity of being human while no longer feeling the power of being healthy and virile

I see a lot of men trying to do the right thing, but life is complicated.

Rod Dreher’s latest post has finally moved me to write. He says with great humility,

We men have a habit of wanting to keep it all in, of telling ourselves to suck it up and get on with life. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but man, I tell you, it can be such a beatdown. As you might recall from my past writing, my ex-wife and I went through ten years of a failed marriage before she finally, without warning, pulled the plug. I feel as if I am having to learn how to walk again. It hurts, and it’s hard to ask for help, and even harder to receive it. I used to be very social, but now, most of the time, I just want to stay at home and read. Is it always going to be like this? I don’t know.

I know a number of men who have been divorced or who are going through one now. I am not picking sides in anyone’s cases. I have no idea what is going on and no one does except the people involved. However, I do know this much: Divorce is expensive, stressful, and emotionally draining. When children are involved, they often suffer. Some men describe the process of divorce in a way that makes it sound truly emasculating.

Let’s face it, it is easier for women to write openly about these things. Not to say that it is painless for us to write about any sadness, trauma, or complex situation, but vulnerability is often seen as a feature of womanhood, not a flaw.

Although there are some men like

who have been writing candidly and vulnerably about their lives for years, there seem to be more men who are finding ways to open up about the challenges they face as men. A couple of months ago , , , , , and worked on a collaborative project about fatherhood that you can find here: also wrote a post called “The men's movement failed; long live the men's movement” atTrying to grow as a man is fraught. We’re squeezed between other people’s judgments: media agendas with their bias against anything masculine or older generations’ expectations with their opposing bias and refusal to accept that their story failed long ago. Which leaves most of us confused. The best we can do is choose to walk alone through a wasteland of fear. T.S. Eliot may not have been talking about masculinity when he wrote The Waste Land, but he could not have described modern masculinity better if he tried. There has to be more to masculinity than this.

“A heap of broken images, where the sun beats,

And the dead tree gives no shelter, the cricket no relief,

And the dry stone no sound of water. Only

There is shadow under this red rock,

(Come in under the shadow of this red rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your shadow at morning striding behind you

Or your shadow at evening rising to meet you;

I will show you fear in a handful of dust.”

Turner offers a solution:

We need stories – vulnerable honest stories of what it means to live – to inspire us to demand more from life. Storytellers can help us build new models for how we’ll find deeper meaning. And we need to believe we can become whole; that we can integrate work, family, spirituality and responsibility with the courage to step into the unknown.

He talks about designing a journey.

One may even say… an Odyssey?

Let’s get back to Homer…

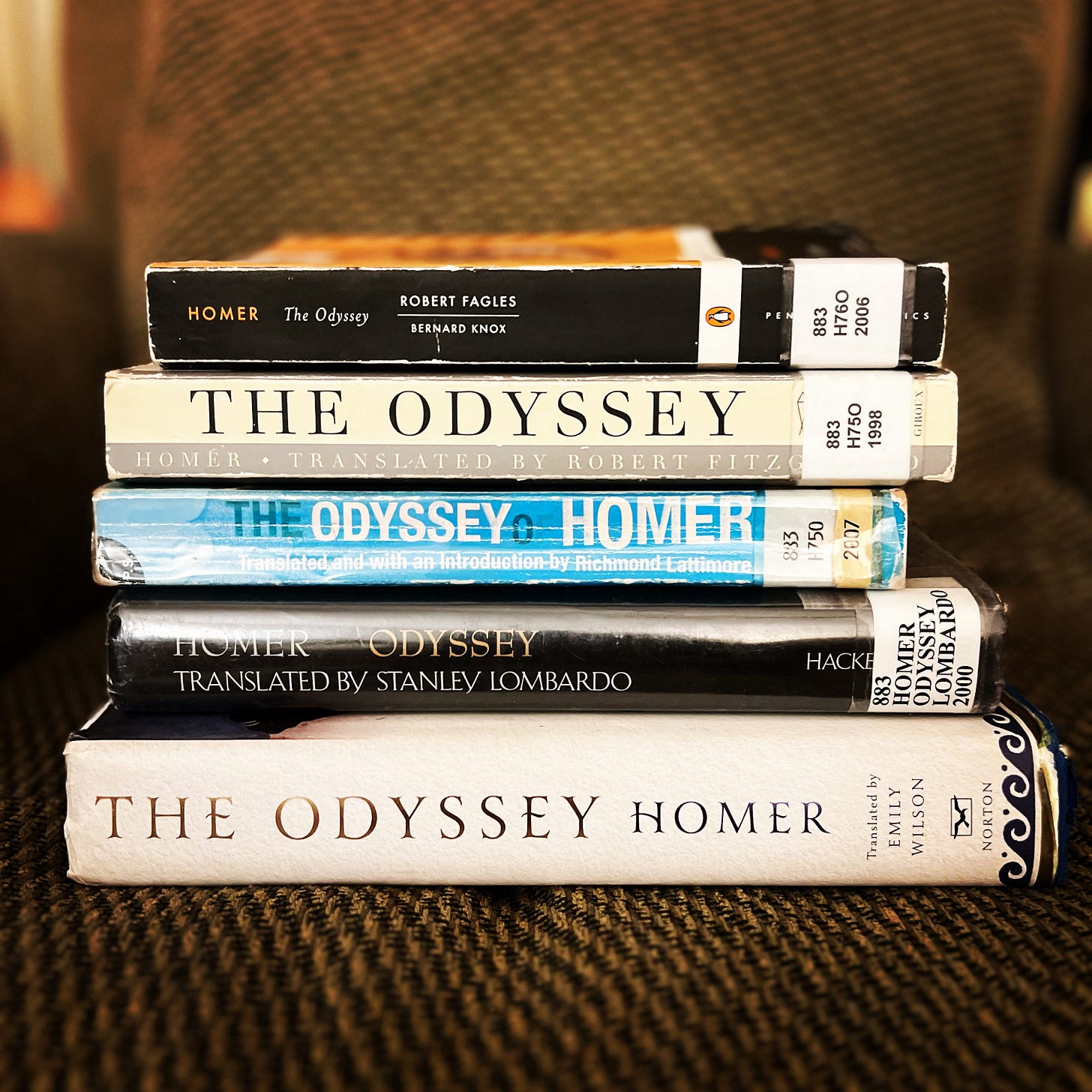

The title of this post comes from the first line from Emily Wilson’s much discussed, loved and scorned 2018 translation of The Odyssey:

Tell me about a complicated man. Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost when he had wrecked the holy town of Troy...

Many people had a problem with Wilson’s word choice for polytropos (Greek: πολύτροπος) which translates into being of many ways, but given the modern backlash against the old heroes of Western culture, I believe “complicated” does capture how modern readers feel about Odysseus. The man was a liar, a merciless killer, and a philanderer. Why would any enlightened person want to think of him as a hero? We can’t see him being a model of modern virtue.

One has to remember that the Odyssey begins, not with Odysseus, but with Telemachus. The poem is not simply about Odysseus’ adventures away from Ithaca and wanting to come home to his faithful wife. The framing of the narrative indicates that this is really a story of why a boy needs a father figure and what the man looks like.

The epic ends in Book 24 with three generations fighting together: Telemachus, Odysseus and Laertes.

Laertes, thrilled, cried out, “Ah, gods! A happy day for me! My son and grandson are arguing about how tough they are!”

But as stories go, The Odyssey tells us about manhood in an oblique manner. In modern times we rely on more explicit instruction in the form of non-fiction. This is why people like

and are so popular.Last month, Rob Henderson wrote a post about “Young Male Syndrome”:

The concept of the young male syndrome was developed by the psychologists Margo Wilson and Martin Daly. And it refers to a pattern of risk-taking behavior that is more pronounced in males in their late teens and early twenties relative to other demographic groups.

Henderson concludes,

But if boys aren’t exposed to positive examples of masculinity in their personal lives, they will look for it elsewhere.

In contemporary western societies, parents, teachers, coaches, local community leaders, and other high-status figures used to raise boys to become men, imparting lessons about personal responsibility, hard work, relationships, and obligations. Today, in the absence of such guidance, many young boys are being raised by viral TikTok influencers peddling diluted and ungrounded conceptions of masculinity.

High-status individuals have a societal responsibility to guide young men toward constructive avenues for status acquisition.

By doing so, they not only help to mitigate the risks associated with the Young Male Syndrome but also contribute to the cultivation of a more balanced and harmonious society.

As a mother of two adult-aged sons I am glad I have a husband who is here to help them navigate this tough world, but I also see how hard it is for a single man to do this. Manhood isn’t the caricature we were told about the guy that never cries. Odysseus cries a lot in The Odyssey. He makes stupid mistakes that get his companions killed. Odysseus is not a perfect man. He’s a complicated one. But he is one who comes back from his failures and trials. He comes back home to the son who needs him.

Every young man is Telemachus.

And every man I have ever met is complicated—but also capable of the heroic.

I really enjoyed this post. And brilliant to use Telemachus as the OG boy bereft of a father. I have two adult sons, 33 and 30, and I was lucky enough to be around for them and continue to be around for then as we are all in NYC.

One of my favorite poems is Tennyson's Ulysses, which is probably one of the favorite poems of many. I thought about how in that poem, Odysseus gets bored at home and decides to once again go wandering.

"There goes Dad again," I can hear Telemachus saying!

Interestingly, I just bought Emily Wilson's translation of The Odyssey for my daughter, who is obsessed with Greek mythology. Though I don't think she ponders the crisis of manhood as she reads! Instead, she has been steeped in empowering narratives like the Rebel Girls series. And she loves Disney films like "Brave," which erect the straw opponent of distant patriarchy only to demolish it with the easy plot of girl power. That's all mostly good for my daughter. I want her to grow up with all doors open to her. But it is not necessarily good for my son, who may someday see himself -- unfairly -- in the role of the oppressor that so many feminist narratives reinforce.

I'd like to hear more stories about men like Marty Ginsberg. How did he navigate the shift from conventional expectations to the more supportive role that he played in his marriage to RGB? Latham is right -- we need guides for those pivots. It's not automatic or obvious.

Every young man is Telemachus, indeed. But many of us who lacked guides in our youth, or who were taught things about masculinity that we try to unlearn, never stop being Telemachus. As a man in the midst of divorce, I feel this keenly. Thanks for keeping the conversation going.