Wishing my traditional Catholic friends a blessed Quinquagesima Sunday. I am a bit of a fan of the old ways, and the Latin naming of the last Sundays prior to Lent evokes a sense of mystery and sacredness that seems elusive these days. Since I married someone with a Polish-Jewish background, I think it has been wonderful for my children so hear prayers said in Hebrew.

I wish my children had more of a formal education in Latin in the way that our Jewish friends learn Hebrew as part of their faith. I read this very interesting article about sacred language, which concludes with the following:

Although the use of a sacred language may challenge us, since it requires us to learn basic prayers in another language, that can be a good thing. It requires more effort on our part that can help us to think through the meaning of the prayer so that we do not simply take it for granted. Using a distinct language provides a sign that the prayer is more important than the words of everyday life. Our Catholic schools used to all teach Latin for a reason (and most public schools did as well for cultural reasons). Learning Latin opens up the great heritage of the Church and the writings of the saints to us. Even just the basic vocabulary can enrich our understanding of doctrine and the Church’s liturgical tradition. Returning even to a limited use of Latin unites us to the past and would serve as a unifying factor for the Church. Even in the modern world, sacred language has not lost its relevance.

Alas, I think this is a hard sell for most people. I hope to study Latin more formally someday. When I was in the fourth grade I had been tapped to join a special group of students who would be allowed to study Latin, and all I needed was a parent signature. When I presented the permission slip to my father he refused to sign it, ripped it up, and said that I was not allowed to study Latin because it is only for priests. I was a bit crushed.

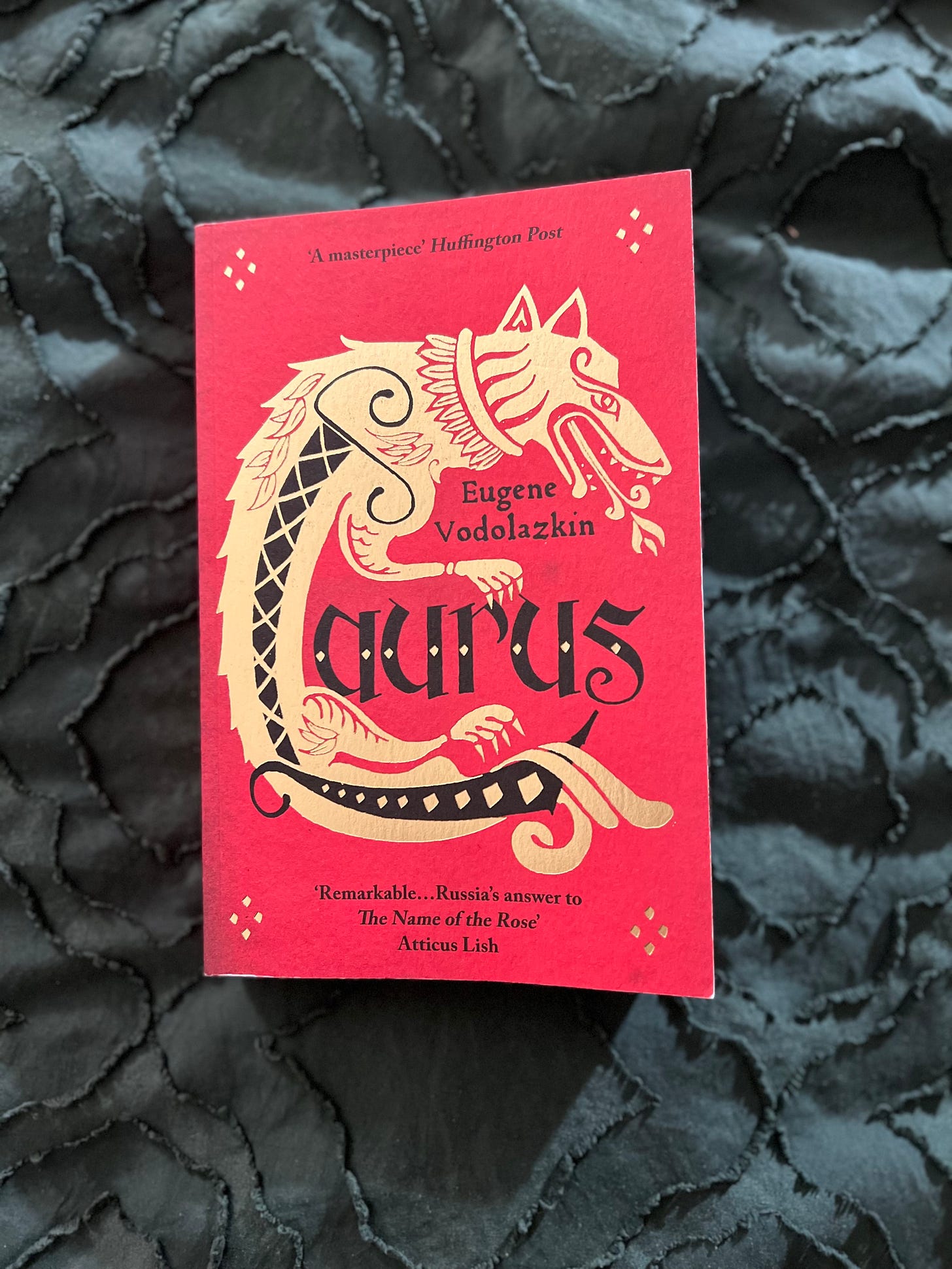

After cross-posting my Lenten reading question on social media it looks like my friends have picked Eugene Vodolazkin’s Laurus. I originally read it with the Close Reads podcast which covered the novel over several weeks last year. You can check out the original reading schedule and helpful links here.

On the off chance that anyone would like to join me in reading, I have posted the schedule below. I kept it light in front so that if anyone wanted to read with me later it would not be so hard to catch up.

Week 1 (February 22-March 4): Pages 3-53 Prolegomenon and The Book of Cognition

Week 2 (March 5-11): Pages 53-97 “It began to smell like spring…”

Week 3 (March 12-18): Pages 97-180 The Book of Renunciation

Week 4 (March 19-March 25): Pages 183-239 The Book of Journeys

Week 5 (March26-April 1): Pages 239 - 291 “In Vienna, Ambrogio…”

Week 6 (April 2-8): Pages 291-362 The Book of Repose

When I read Laurus last year I found a compelling parallel to C. S. Lewis’s Four Loves. If you have not read Laurus you may not want to read on because the text below contains spoilers, but I thought I would include some of my thoughts for those who who don’t mind or have read the book.

The Book of Cognition, Storge and Christofer

The first depiction of love is the relationship between Arseny and Christofer which shows storge, familial or empathy love. Arseny (who was born on the feast of St. Arsenius) is cared for exclusively by his grandfather Christofer. It is in childhood that we first encounter our experiences with love, and it is significant that part of how Christofer loves is by imparting him with knowledge and teaching young Arseny how to heal. The name Christofer also foreshadows the image of the saint known for bearing a young child Jesus to safety (echoed in the last scenes of the novel).

The Book of Renunciation, Eros and Ustina

Romantic love can be the most perilous of all the loves as it becomes so easily distorted by the sin of lust. Arseny meets Ustina whose name comes from the East Slavic Latin word for “justified”. However, Ustina and her child receive no justice as Arseny denies her marriage, a last confession and the care of a midwife—all of which leads to her physical and spiritual demise. One can presume that Arseny did not want to reveal his own sin to the community because of his pride. Due to his grief and burden of guilt he ultimately renounces his fame as a healer and a chance to live a life with another woman and son and chooses a life of privation by becoming the holy fool Ustin.

The Book of Journeys, Philia and Ambrogio

The Book of Journeys is my favorite part of the novel, mostly due to the character of Ambrogio (named after St. Ambrosius) who helps Arseny understand the boundless nature of time. Up to this point Arseny was without any true and close friends. Through this pilgrimage Arseny and Ambrogio endure a journey to Jerusalem and become close. Arseny develops an affection for Ambrogio whose life is cut down before reaching the holy site. It is worth mentioning that Ambrosia means "immortality" in Greek -- derived from the Greek word ambrotos ("immortal"). Although Ambrogio is certainly not immortal, his visions made him seem unbound by time, thus making him, in a sense, perpetual. It is no wonder that Elder Innokenty gives Arseny the name of Amvrosy (i.e. the Russian equivalent of Ambrogio) again taking the name of the person with whom he encountered a type of love.

The Book of Repose, Agape and Anastasia

Finally we are brought to agape, unconditional godly love. Although I know Vodolazkin is Orthodox, I have to mention that the Catechism of the Catholic Church defines "charity" as "the theological virtue by which we love God above all things for His own sake, and our neighbor as ourselves for the love of God." Thomas Aquinas wrote that "the habit of charity extends not only to the love of God, but also to the love of our neighbor." This fits perfectly with Laurus’s encounter with Anastacia whose name means “resurrection” and Laurus’s name means “triumph” but it also sounds like Lazarus. The elder Laurus does all the things he had failed to do as the young man Arseny, by saving Anastacia and her unborn son. He also saves the mother's soul by denying her an abortion. In contrast to the young Arseny of the past, Laurus claimed Anastacia as the mother of his child at the expense of his reputation in order to save her life from the mob. When she is in labor he attempts to find a midwife. And finally, with a healthy infant boy in arms, Laurus passes away peacefully having corrected the spiraling path into a full circle. His death echoes the image of Christofer, the grandfather and the saint.

As G.K. Chesterton had said, “The way to love anything is to realize that it may be lost.” By experiencing grief from losing the people he had loved, Laurus was able to recognize the fourth and divine form of love: agape. And perhaps he found it in such a perfect form that it made him a saint.

I look forward to reading Laurus again, and over the course of Lent I may have more things to say about the book. Rereading great literature always turns up some surprising new connections that one does not pick up the first time around.