Memorization, or "to know by heart..."

If what we remember can transform our minds and souls then why don't we memorize anything anymore?

Our culture has an interesting attitude toward memory. We think of people who recall vast amounts of information as having some type of super power. We see memory as something that we could lose. Or as something that haunts us. We are nostalgic for childhood memories. And we feel trauma from bad memories.

Elie Wiesel once wrote,

Without memory, there is no culture. Without memory, there would be no civilization, no society, no future.

But the act of memorizing is work. In the past American education relied on rote memorization as a main method for learning lessons, like times tables, parts of speech, Latin conjugations and declensions, states, countries and capitals, etc. Many people who were students when this method was de rigeur were taught by teachers to do well on a test, but not taught well enough for comprehension or long-term retention. At some point rote memorization was tossed from the education toolbox. Those who currently have children in school know that memorizing is no longer a priority, even among our younger students who are the ones most able to recall random facts with facility.

With the advent of smartphones, we ask less and less of our memory than previous generations. We do not have to recall phone numbers, birthdays, or addresses. With GPS we no longer need to remember how to get to places which often means knowing landmarks and street names—things that make us more aware of a place’s geography and history.

Remembering is incidental. Memorizing is a choice. And it is a skill.

Aeschylus is thought to have said that Memory is the mother of all Wisdom. Is our society starving Wisdom by not feeding Memory?

Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, was also the mother of the Muses: Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (history), Euterpe (music and lyric poetry), Erato (love poetry), Melpomene (tragedy), Polyhymnia (hymns), Terpsichore (dance), Thalia (comedy) and Urania (astronomy).

Most art requires memory. Dancers need to drill choreography. Musicians need to memorize music. Actors need to know their scripts. And many great poets and thinkers have many verses committed to memory. Memorization of words is not just in the mind, but in the muscles. When you no longer have to think about the words or the music or the movements, you can then feel them on a deeper level. The first step in memory is to know what you are memorizing. The second step is to know what it means. The third step is to know how it feels.

Poetry was born out of the need to remember. Without the widespread technology of writing, stories needed to be passed down orally in order to survive. Rhyme, meter, and imagery aided the poet who could then recite long passages to audiences.

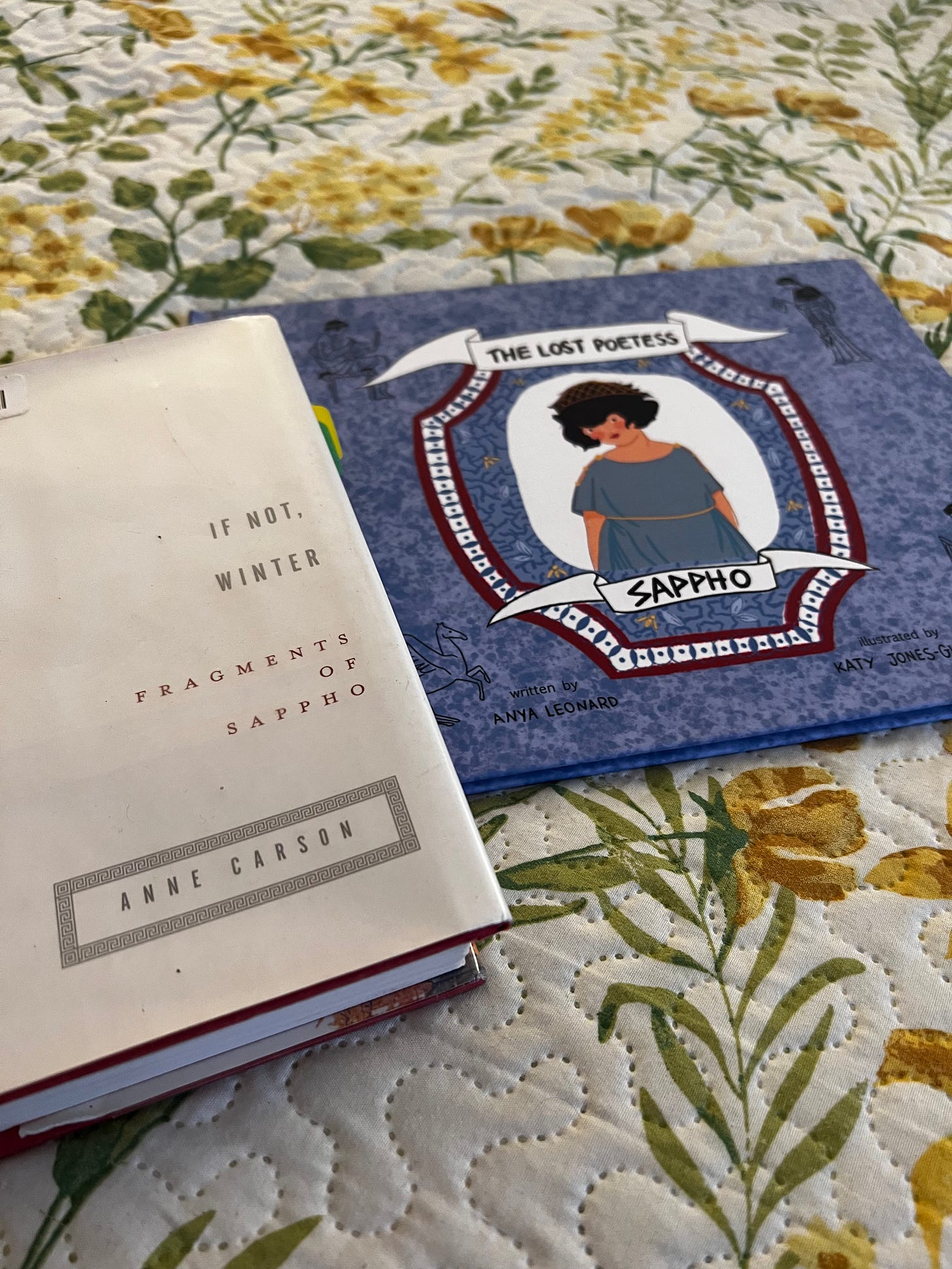

A lot of beautiful poetry has been lost—like the work of Sappho. My youngest and I have been reading about her (with thanks to

‘s Anya Leonard and her lovely picture book). Sappho’s poetry exists primarily in fragments, but she was once one of the most influential poets of the Greek world. Homer was the poet and Sappho, the poetess. Influential contemporaries had memorized her poems. However, during her lifetime she became less popular. It is quite possible that had she not fallen out of favor her poems would have survived more intact.To preserve the memory of another is an act of respect, and if a culture doesn’t honor an artist then chances of their survival diminish. However, beauty has a way of attracting attention and being found. When we find that beautiful thing we need to replicate it and share it, lest it be lost.

When I was a little girl I learned the words of a prayer out of my own desire. I simply loved the sound of the words and the message. It said so much of what I wanted to be: loving and forgiving, joyful and consoling.

The Prayer of St. Francis

Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.

Where there is hatred let me sow love;

Where there is injury, pardon;

Where there is doubt, faith;

Where there is despair, hope;

Where there is darkness, light;

Where there is sadness, joy.

O Divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek

To be consoled as to console;

To be understood as to understand;

To be loved as to love.

For it is in giving that we receive;

It is in pardoning that we are pardoned;

And it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.I chose the words of St. Francis for the very first episode of Poetry Mixtape, which I just published this past Friday. Most people do not normally think of prayers as poems, but many religious works have the form and cadence of poetry. Six of the books of the Bible are poetry—Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, and Lamentations. The repetition of litanies has a poetic cadence. The occasional rhyming prayers are still popular with even the most erstwhile Catholics, albeit for practical reasons,

St. Anthony, St. Anthony, Please come around Something is lost And cannot be found.

And this favorite of my mother-in-law,

Hail Mary, full of grace, Please help me find a parking space.

One of the benefits to being religious is that memorization is built into our daily lives through prayer. Just by pure exposure and repetition, all my children at a young age have been able to learn prayers by heart. If Catholic families pray the rosary together the children should be able to remember the Apostle’s Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary and the Glory Be. Although the desire to remember is not in the children, it is the community that has the embedded desire to perpetuate the culture.

Many religious cultures will have beautiful rituals that come in cycles, repeating as if knowing human’s tendency to forget.

Without memory, there is no culture. Without memory, there would be no civilization, no society, no future.

— Elie Wiesel

I will be specific in what I am asking us all to remember: POETRY. Much of it is made—you might even say verbally engineered—to be remembered.

Try it. Start with just one poem. Go short and low brow with a limerick. Or go classy with a sonnet. Shakespeare is always impressive. If you know the Gilligan’s Island theme, then Emily Dickinson should be a breeze.

When you are at a loss for words—when the world defies logic or compassion—a poet has probably written the essence of what you want to say. In June, when another ship of asylum seekers sank off the coast of Greece I could recite Stallings. When Putin invaded Ukraine I could recite Auden. At the anniversary of the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima I could recite Sadako Kurihara.

And Mary Oliver’s wild geese and grasshoppers have become shared metaphors between me and my teenager.

Randomly I will ask my daughter, “Who made the world?”

“Who made the swan and the black bear?” she answers without looking up from whatever she is doing, from wherever she is in the room.

“Who made the grasshopper?” I ask. “This grasshopper I mean—”

And it goes on and on, the two of us like birds divided by a river called a generation. A call. A response. Like our church’s responsorial psalm between mass readings. A sacred family ritual of remembering a poem together.

It ends with me asking my daughter, "Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

Someday, when I am as dead as Sappho, my daughter may start losing her memories of me, but when she comes across “The Summer Day” on print or aloud I hope my voice comes back to her—telling her to keep living her one wild and precious life.

This is why we need poetry.

This is why we need to memorize it.

What a lovely practice with your daughter! Yes to everything about this post!

I happened to come across this piece while browsing Substack with my morning coffee. It was recommended by a publication I follow on the platform. What a beautifully written tribute to the importance of poetry and its legacy. I had to fight back a few joyful tears while reading. What a gift this was, getting to read this article. Thank you <3