A Fulsome Ides

The Tragedie of Guernica. Just because you are stabbing Caesar doesn't mean you are saving the Republic.

The origin of every fortune is a crime.

The ides of March are a dangerous time.

from David Lehman’s “The Ides of March”

Friends, Romans, subscribers,

Thank you for visiting on this portentous day on the calendar: The Ides of March.

I shall not be giving you a briefing on the significance of this day, since many of my friends have done it for me. Here are a few fun links for you:

- has an article about the death of Julius Caesar as a historical event

- gives us a close reading of David Lehman’s poem “The Ides of March”

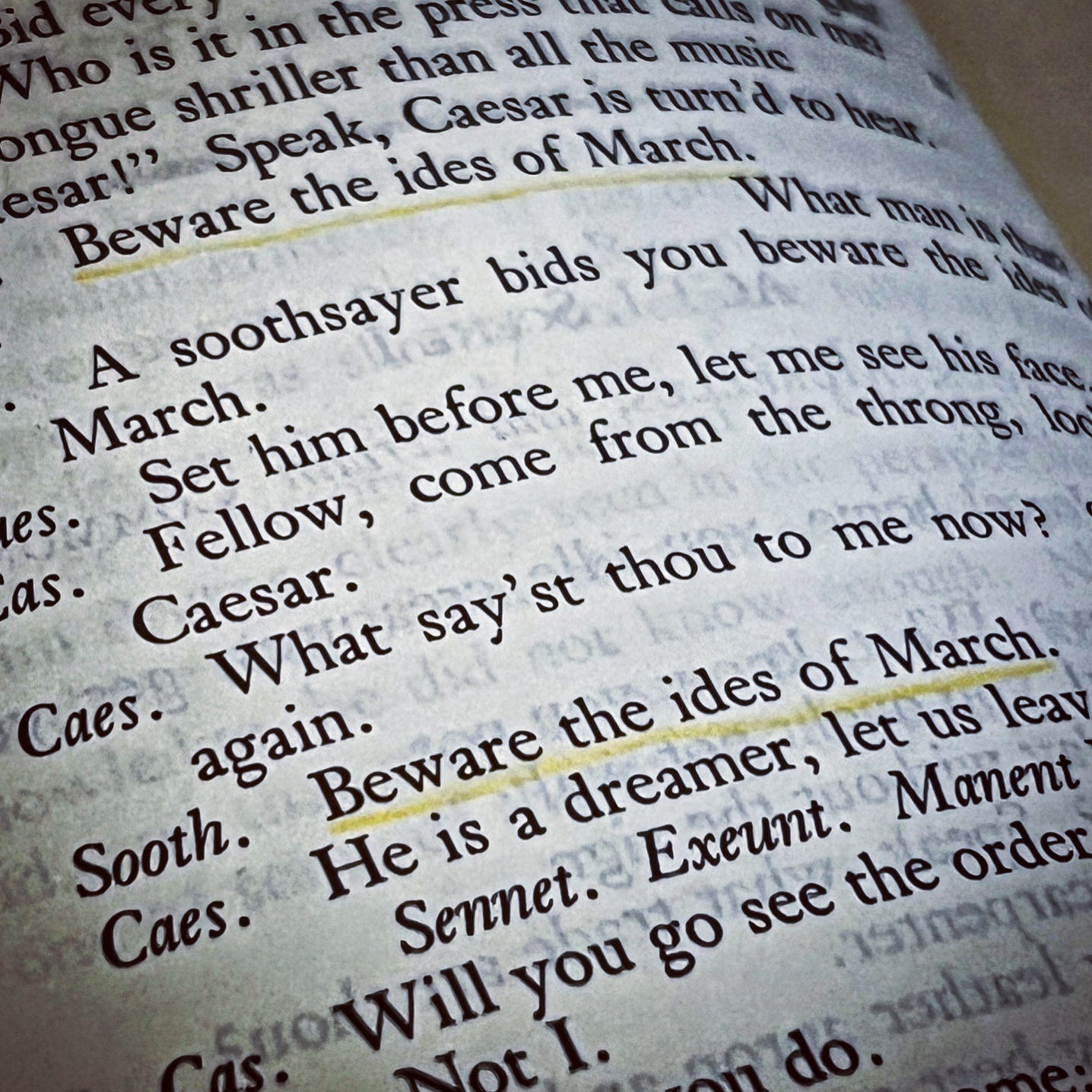

- breaks down the Shakespeare, doing an analysis of the speeches of Brutus and Antony from The Tragedy of Julius Caesar

For good measure, I give you one of my favorite recitations of Antony’s speech by the Damian Lewis:

My appreciation of Jenn’s post should be no surprise seeing as I am in the middle of my sonnet project, The Beauty of Shakespeare. Although I would like to note that

at her Substack, The Priory (as if she could name it anything else) has done excellent deep dives into some handpicked sonnets, like 18, 55, 73, 116, 130, and 138.Lately, my news feeds have delivered something other than Roman history and Shakespeare but just as ominous as the Ides: the cancellation situation at Guernica.

at writes a good summary of the situation on her recent post:This week, a scandal rocked what’s left of the literary world. Guernica, a long-respected journal, bowed to pressure from its all-volunteer staff and on Monday retracted an essay it had published on March 4 (an archived version can be found here). “From the Edges of a Broken World,” written by Joanna Chen, a British-born Israeli who works as a translator of Hebrew and Arabic literature and for years has driven Palestinian children from the West Bank into Israel for medical care, describes a torrent of conflicted emotions in the aftermath of October 7.

I have read the essay and chatter surrounding it. Joanna Chen is a very good writer, and I encourage everyone to read her work in full. Unfortunately, the staff at Guernica felt differently and staged a public protest and mass resignation, which caused the literary magazine to archive the essay and publish the following statement:

Guernica regrets having published this piece, and has retracted it. A more fulsome explanation will follow.

Such an odd word to use, isn’t it? It is so novel that it must have been chosen deliberately and yet, according to Dictionary.com, “fulsome” is an adjective that has quite the range of definitions:

offensive to good taste, especially as being excessive; overdone or gross: fulsome praise that embarrassed her deeply; fulsome décor.

disgusting; sickening; repulsive: a table heaped with fulsome mounds of greasy foods.

excessively or insincerely lavish: fulsome admiration.

encompassing all aspects; comprehensive: a fulsome survey of the political situation in Central America.

abundant or copious.

As of this writing, no such fulsome explanation has been published so I can’t tell what meaning the editor was going to go with, but in the meantime you can bide your time by reading some commentaries at the Los Angeles Times, The Atlantic, The Nation, and The New York Times.

Coincidentally an article was published this morning from The Washington Post about Picasso’s 1937 masterpiece from which the journal Guernica gets its name. The WP laid out the historic event that inspired the art:

The bombing of Guernica was intended by Hermann Göring, commander in chief of the German Luftwaffe, as a birthday gift for Hitler. The attack was delayed by several days because of logistical issues, but Hitler was pleased nonetheless. The plan was to maximize civilian casualties. Col. Wolfram von Richthofen, who was in charge of the attack, achieved this by pausing after a brief initial bombing, then, after civilians had come out of their shelters, launching a devastating second wave. People were trapped in the open, incinerated, asphyxiated and strafed with machine-gun fire. An estimated 1,500 civilians were killed. Guernica was leveled.

Sounds familiar. An atrocity that focussed on civilian deaths. Dresden, Hiroshima, 9/11, Ukraine, October 7, Gaza…

But read Chen’s essay. She doesn’t condone violence or militarism.

At all.

In a statement to The LA Times, Chen said,

“Removing any stories and silencing any voices is the opposite of progress and the opposite of literature.”

“Today, people are afraid to listen to voices that do not perfectly mirror their own,” she said. “But ignorance begets hatred. My essay is an opening to a dialogue that I hope will emerge when the shouting dies down.”

Critics of the essay accused the essayist of “both-sidism” but the problem is that there are many sides because there are many people, and in the end they all have to live with each other if there is ever a time of peace—which I certainly hope will be the case.

In The Atlantic, Phil Klay, National Book Award winner and former Marine who served as an officer in the Iraq War, writes that the retraction of Chen’s article is “a betrayal of the task of literature, which cannot end wars but can help us see why people wage them, oppose them, or become complicit in them.”

Empathy here does not justify or condemn. Empathy is just a tool. The writer needs it to accurately depict their subject; the peacemaker needs it to be able to trace the possibilities for negotiation; even the soldier needs it to understand his adversary. Before we act, we must see war’s human terrain in all its complexity, no matter how disorienting and painful that might be. Which means seeing Israelis as well as Palestinians—and not simply the mother comforting her children as the bombs fall and the essayist reaching out across the divide, but far harsher and more unsettling perspectives. Peace is not made between angels and demons but between human beings, and the real hell of life, as Jean Renoir once noted, is that everybody has their reasons. If your journal can’t publish work that deals with such messy realities, then your editors might as well resign, because you’ve turned your back on literature.

“Removing any stories and silencing any voices is the opposite of progress and the opposite of literature.” - Joanna Chen

At the end of

’s Ides of March post the author, Barry Strauss, concludes:There are many lessons to be learned from the stirring and terrible events of the era of Caesar and Augustus. One is the law of unintended consequences: the men who killed Caesar on the Ides of March thought they were saving the Republic, not hastening its end. The other is the need for political sagacity, for fine-tuned political skills, in order to persuade people to accept reform. And finally, we can’t overstate how fortunate we are to live in a society where political disagreements are settled by debate and not by arms, by ballots and not bullets.

The tragedy is that we are not as fortunate as the Strauss’s essay would have us believe. The case at Guernica is proof of that. The volunteers who protested the essay and quit are not saving Palestine or literature. They are participating in an act of assassination that they think is for the good for the people. And some, dare I say, may be doing this for the sake of their own egos and reputations within their elitist intellectual enclaves.

On Strauss’s second point we also find political sagacity lacking. Hardly anyone believes in political compromise anymore—the art of the possible—which is one of the ways that we may have a chance to find a tolerable solution to this.

And the third point about how we live in a society where political disagreements are settled by debate and not by arms, by ballots and not bullets. Make no mistake, those protesting the essay are not interested in debate. They are engaged in the silencing that they accuse others of doing to them. The age of cancellation has ruined people’s reputations and livelihoods. And yes, it kills people.

The Ides of March always comes around, like a ghost who is trying to remind the living of what treachery humans are capable of. And remember, the senators who murdered Julius Caesar ultimately did not fare well themselves. Those who hold the dagger are short-sighted.

Caesar entered the Senate knowing what could happen to him, but he was not going to live in fear.

It seems like writers with any type of backbone will need to write with the same amount of fatalism if they truly care about the future of literature, culture, and society.

Very insightful piece, Zina! And a curious scandal. Definitely agree with this part: "It seems like writers with any type of backbone will need to write with the same amount of fatalism if they truly care about the future of literature, culture, and society." One issue is certainly that there are too many writers who are careerists, not fatalists. I give the careerists a hard time every now and then over at Timeless. :P I just found a biography of Jose Rizal at a bookshop: talk about a fatalistic writer!

Unfortunately, I don't think debate will bring the two sides together at this stage. And I don't think it ever has with Israel and Palestine: the rise of this sizeable faction of pro-Hamas people in the US proves that the sentiment for further debate is almost nonexistent at this point. The reason why neither this nor the partisan divide in the States can be resolved is simple at heart: both sides know too much. And we want pain and suffering to be inflicted upon the other side to punish them for their "sacrilege." Ideally a maximal amount of pain.

How does one combat this kind of socio-political sadism? I'd like to think literature can help.

After reading the essay that created the storm of hysteria, I can only think that nuance is officially dead.